Hands Down

There’s a literary device called synecdoche, in which a part of something is used to represent the whole. The example that’s usually taught in school is “head of cattle,” a phrase that refers to the whole animal, not just its head; but I’ve never liked that example, because the phrase also contains “of cattle,” which makes it less than pure synecdoche.1

A better example is the use of “hand” to represent a person, as in “ranch hand” or “stagehand.” I find that use of synecdoche particularly significant, because for me, a person’s hand physically does represent the person. I’ve always paid close attention to hands, to the extent that I tend to recognize and remember people by their hands.2 There have been a few occasions when I’ve been reunited with an old school friend whom I haven’t seen in thirty or forty years, and I feel awkward because their face has changed so much as to be virtually unrecognizable; but as soon as I look at their hands, I immediately relax — “Ah, yes, that really is So-and-So.”3

Even better is if I can feel someone’s hands as well as look at them. Unfortunately, as I talked about in “People Say Things,” our society offers very little opportunity to touch each other. Usually all I get is a handshake, which allows me to take at least a brief impression, but in the age of the coronavirus, even that opportunity seems like it’s gone away permanently.

When I go to movies, I tend to sit very close to the screen, mainly because I like to be immersed in the action — I want it to take up my whole field of vision. But another advantage of sitting that close is that I have a really good chance to see the actors’ hands. Looking at their hands is a way to get beyond the artifice of lighting and makeup and costumes, to get a visceral reminder that those were living, breathing people in front of the camera.

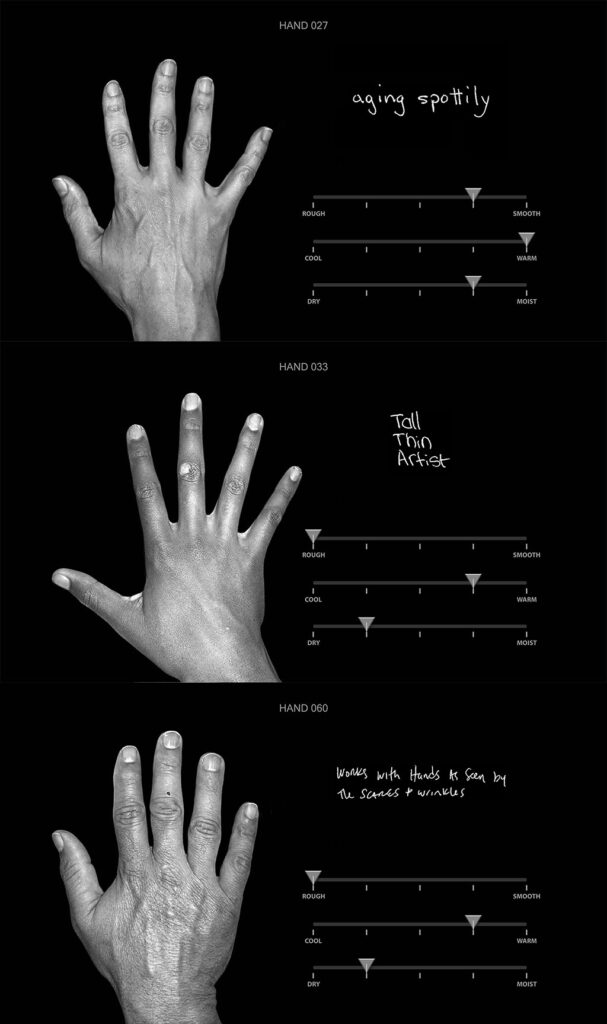

My attention to hands tends to show up in my creative work. More than ten years ago, I did a project called “100 Hands,” which took the form of a black-and-white computer display that pulled up random data screens containing photos and quantified assessments of people’s hands. (I especially liked making that, because it gave me a chance to hold one hundred people’s hands and record my pseudo-scientific impressions of their temperature, texture, and degree of moisture.)4 More recently, I made “Humandala,” a sort-of mandala made up of body parts, and “Simple Dancers,” a series of images in which dancers are reduced to their most elemental components — hands and feet. This year, in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, I was inspired to make “Chain of Hands,” for which I asked people to send me “hand selfies” from wherever they were sheltering in place, and linked them into a long, unified chain. Not only did that project give me something useful to do during that long lockdown period; it also helped me feel connected with my friends, because (at least virtually) I had their hands in front of me.5

As much as I rely on people’s hands to give me a sense of who they are,6 there’s a part of me that knows that it’s only an illusion. There’s an old saying that “the eyes are the windows to the soul,” and we do so often get the feeling that when we look into someone’s eyes, we’re seeing deep down into their essence. In reality, while we certainly get lots of subliminal information from minute changes in the size of people’s pupils, we’re not literally seeing inside them.

I’m sure it’s the same with hands. I genuinely sense, when I look at or feel someone’s hands, that I’m getting a glimpse of something beneath the surface. I have to always remind myself that a person’s bodily appearance — whether hands or anything else — does not reveal anything about who they really are. As with eyes, I’m sure that that tiny changes in a hand’s muscle movement, blood flow, and amount of moisture are giving me a sense of someone’s emotional state from moment to moment, but there’s no rational way that a person’s hands can reveal anything essential about them. Still, it feels like they do. I can’t help it. I hope, once this pandemic is over, that I’ll once again be able to get close enough to people to see their hands.

- My favorite example of synecdoche is “your ass,” as in “get your ass out of here,” but I don’t think they’d want to teach that one in school.

- This is one reason why I’m bothered by people wearing nail polish — I find it frustrating not to be able to fully see what their hands look like.

- At this point, you’re probably wondering, “Why all the footnotes”? Well, back when I wrote “Game / Show,” I got a WordPress plugin that allowed me to insert a footnote, and I haven’t had a chance to use it since then. So today I let myself go crazy. I promise this won’t happen again.

- The other projects mentioned in this paragraph can be seen in my online gallery, but “100 Hands,” which was built using now-obsolete Flash technology, can no longer be displayed.

- Long before any of these projects, there was a mime sketch that I developed in college. It was called “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” and was accompanied by the Beatles song of the same name. It starts out as an apparent romantic comedy, as a man notices an attractive young woman and engages in a series of futile attempts to take her hand in his. At the end, frustrated, he pulls out a knife and slices through her arm at the wrist, so he can literally hold her hand. I know that this wouldn’t play very well today, but trust me, people thought it was funny in the 1970s.

- I have this experience not only with hands, but with feet. I hesitate to mention this, because any attention to people’s feet is generally associated with some sort of sexual fetish. (Interestingly, I read recently about the theory that the prevalence of foot fetishes might be related to the fact that the area of the brain that’s associated with feet is right next to the area associated with genitals, and that there may be some stray signaling between the two areas.) In any case, the only reason I’ve included this information is that I wanted the opportunity to put it in — wait for it — a footnote.