Display Case

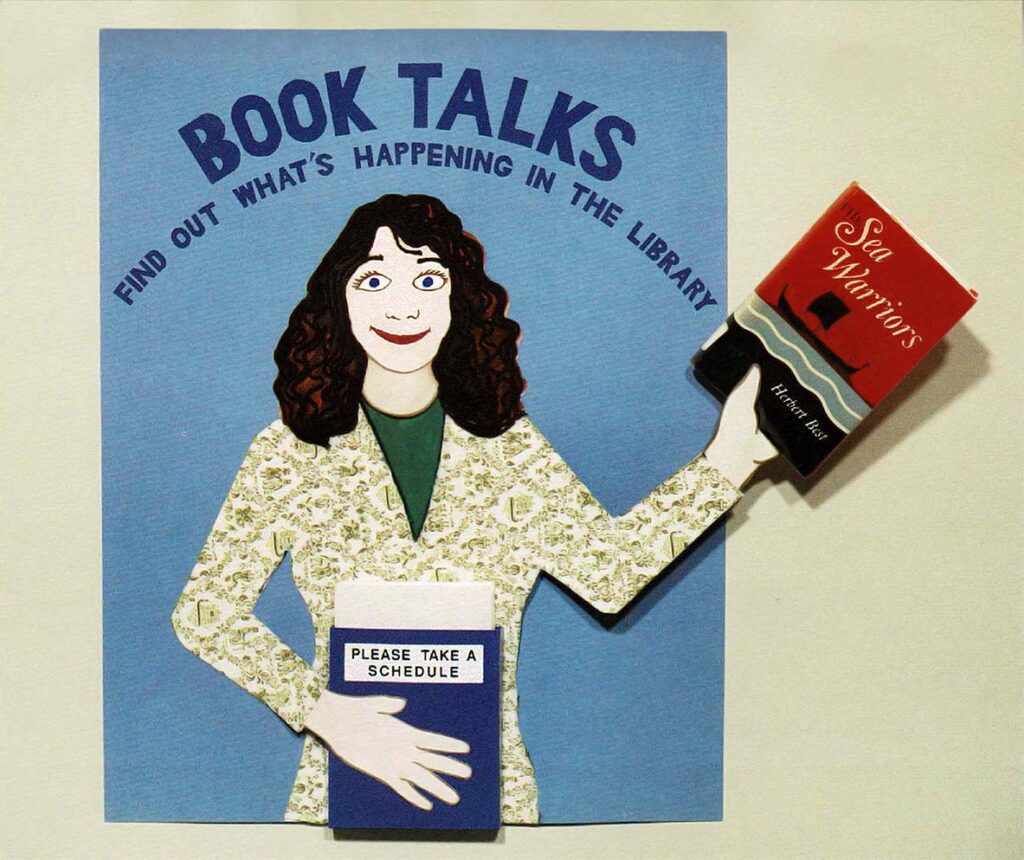

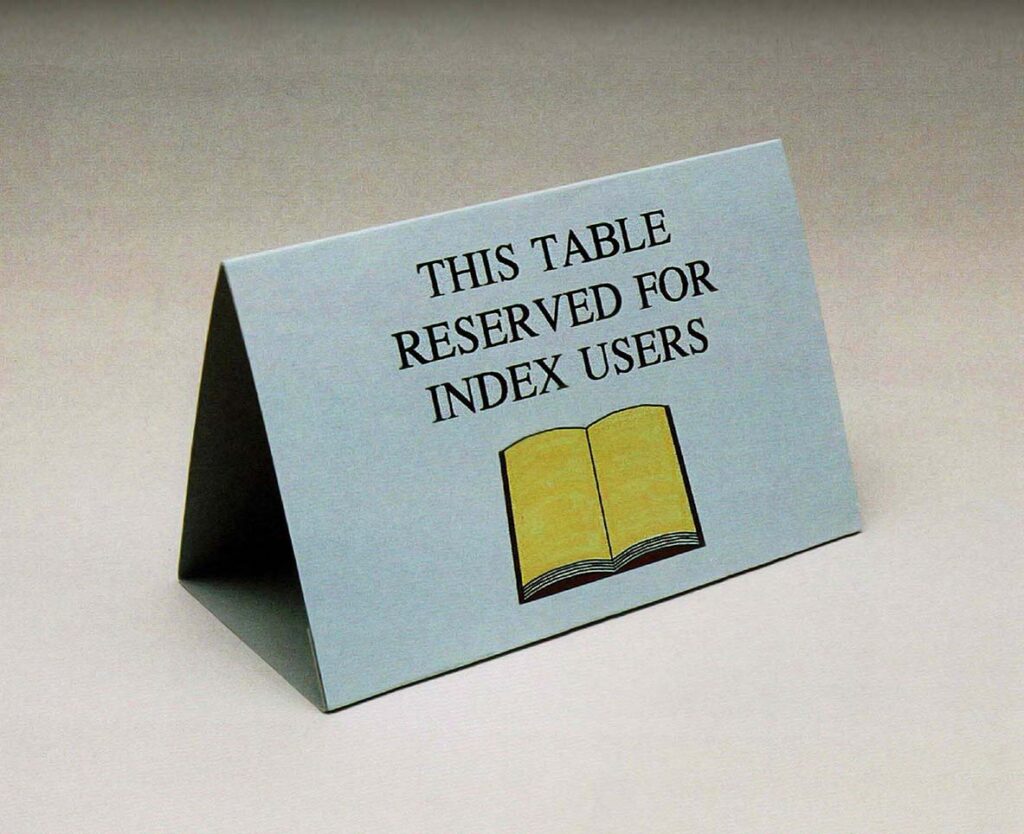

The Library Displays Handbook, published 30 years ago this month, was the first book to sport my name on the cover. I wrote the text, collaborated on the design, created the illustrations, and built a variety of large and small library displays that were reproduced in a color insert. (You can see a couple of samples at the bottom of this post.)

I did all this as a work-for-hire under contract to the H.W. Wilson Company — a publishing house that catered exclusively to libraries and librarians, best known in those days for the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature — so I never received any royalties, and have no idea how well the book sold. It’s apparently still available on Amazon, although it’s listed as “Temporarily out of stock,” and it’s accompanied by a single one-star review that says “Too old to be useful.”

For the most part, I can’t argue with that review. The section called “Computer-Generated Lettering” talks about the relative pros and cons of daisy-wheel, dot-matrix, and laser printers, and spends two dense pages expounding on the technical knowledge required to use a laser printer. (“Commands to a LaserJet must be expressed in the Hewlett-Packard Printer Control Language [HP PCL], while commands to a LaserWriter must be expressed in the PostScript Page Description Language [PostScript PDL].”) Later, the book notes that computer-generated text and graphics are generally limited to black and white, since any sort of color printer would be beyond the budget of most school or public libraries.

Other sections describe now-antiquated tools such as rub-on lettering, Kroy lettering machines, photomechanical transfers, and hot-wax machines for paste-up. Photocopying is described as a technology that only recently has become widespread and affordable. (“Self-service copy shops have become increasingly common in recent years; most communities have at least one, and some communities have dozens.”)

Surprisingly, however, much of the book is not dated at all. The whole first chapter introduces the elements and principles of design, which certainly haven’t changed since 1991. Many of the techniques and sample projects involve the use of timeless tools and materials such as paper, scissors, paint, and glue. The Construction chapter demonstrates how to make a book stand out of a wire hanger, how to make a sturdy shelf out of cardboard, or how to make a concealed picture-hanger out of thumbtacks and cloth tape.

The only reason that I — a non-librarian — felt qualified to write such a book is that I’d spent my whole life practicing these sorts of techniques. By the time I was eight years old, I was able to cut letters and numbers freehand out of construction paper, or quickly make a hinged-lid box out of shirt cardboard. I routinely won poster contests in elementary and high school, and earned a nice supplemental income in college by making signs for the university’s food-service department. As a project director at a small educational publishing company, I often hired myself as a freelancer to create graphics and props for books and filmstrips. The library side of the project felt familiar as well; I’d spent much time in libraries (and had briefly dated a librarian), so I had a pretty good sense of what the handbook needed to cover.

But if so many of the techniques for hand-crafting library displays are timeless, why does the book feel — in the wise words of that Amazon reviewer — “too old to be useful”?

Part of it, I suppose, is how the nature of a public library has changed in 30 years. The handbook dates from a time when people still went to libraries to acquire printed books, which they found by thumbing through individually typed cards in the card catalog. They’d read newspaper articles on microfilm or microfiche, and magazine articles in actual issues of the magazines themselves, using hardbound indexes such as H.W. Wilson’s Readers’ Guide to find the topics they were looking for. In such a physical and tactile environment, posters and displays made out of cardboard, paint, glitter, and yarn didn’t feel out of place.

The nature of librarianship seems to have changed as well. The profession has become more specialized and technical — many library schools have rebranded themselves as schools of “information science” — to the point where creating hand-crafted displays would not meld easily with the responsibilities of the 21st-century librarian.

Mostly, though, children’s upbringing has changed. I’d guess that — like me — most people who grew up in the ’50s or ’60s had some experience making things out of paper, paint, and glue (not to mention pasta, popsicle sticks, and pipe cleaners). It was a common pastime at summer camps, at scout meetings, and in school art classes. Later, these materials remained familiar to us as adults, and we were able to make use of them when the occasion arose. Today’s young adults grew up in a largely digital environment, where the chief purpose of hands is to push a mouse and type on a keyboard.

Interestingly, in response to the increasing digitization of childhood, some elementary schools have begun to offer “maker spaces,” where students can use physical materials to create artistic or practical objects. Perhaps in the future, the Library Displays Handbook will be seen not as obsolete, but as ahead of its time.

I hear that in figuring out what to do when you grow up, or retire, it’s often a good idea to hearken back to what you did as a kid that you loved. I didn’t realize that you had that covered!

Your book talk sample display is adorable! Is that a portrait of Debra?

It wasn’t intended to be, but now that you mention it, I can see the resemblance!