Atmosphere (2)

(part two of four)

It was taken for granted by young people in the 1960s, who would routinely describe a person as giving off “good vibrations” or “bad vibrations,” that all of us radiate — or emanate — something of ourselves. Put enough people together who are sharing a feeling or having the same experience — particularly in a place such as a theater or a church, which is designed to encourage that common experience — and those emanations build on each other and reinforce each other, creating what we might call a very strong atmosphere.

We often talk about going to a particular café or restaurant because “it has a good atmosphere.” But what we tend not to notice is the aliveness and potency of atmosphere. Think of those occasions when many people come together for a common, deeply felt purpose — a funeral, a political rally, a celebratory meal — where you can’t help but feel the atmosphere, even in moments of silence. My entrance as a mime into a darkened theater — described in part 1 of this post — gave me an opportunity to experience that kind of atmosphere in its purest and simplest form.

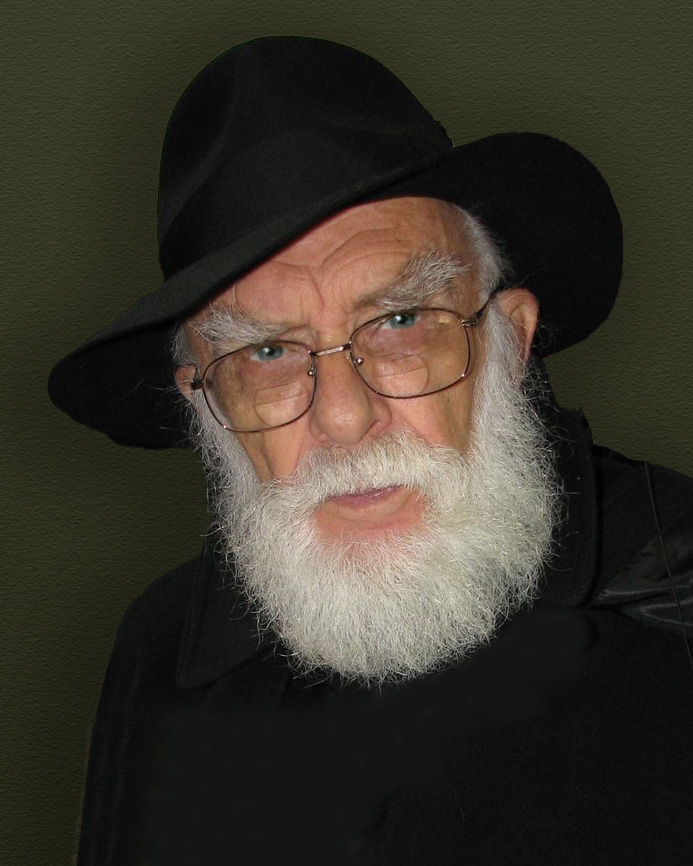

A few years after that mime performance, I attended a lecture by the (now sadly deceased) magician and professional skeptic James Randi. I had been a fan of Randi’s since I was a kid, when, as The Amazing Randi, he had often performed baffling illusions and Houdini-like escapes on television. By this time, he — like Houdini, late in his own career — had largely given up doing magic and had devoted himself instead to debunking the claims of self-proclaimed psychics.

Randi’s mission, he told us, was to subject all claims of supernatural powers to the cold light of the scientific method. His experience as a magician had made him intimately familiar with the tricks that fraudulent psychics could use, and he worked with scientists to design experiments that would guard against such tricks. His lecture was filled with stories about so-called clairvoyants, telepaths, and mentalists who were unable to replicate their feats under his carefully controlled laboratory conditions. When confronted with their failures, they tended to give similar excuses: “My power is sensitive to outside interference — it doesn’t work when there are nonbelievers present,” or “I just can’t relax in this hostile atmosphere.”

Randi himself professed to be agnostic about supernatural powers: he’d be perfectly willing to accept their existence if he saw convincing scientific evidence. But there had, so far, been no such evidence. And given its absence, Randi found it frustrating that people were continuing to call themselves psychics.

Like Randi, I believed then that the only way to understand the world was through reason and logic. Just as I would have dismissed anyone’s claim to have psychic abilities — because the existence of such abilities hadn’t been scientifically proven — I dismissed all belief in mysticism, spirituality, and religion. I often had debates with religious friends, trying to convince them that belief in God was irrational. (As a junior philosophy major, I wrote a paper demonstrating why God can’t logically be omniscient and omnipotent at the same time.) As an actor and a mime, I celebrated emotion, humor, beauty, spontaneity, and other irrational aspects of life; but I saw these as merely human characteristics, ultimately meaningless, with no power to lead us to what was true about the world.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that I had a hard time making sense of the experiences I’d had at the beginning of those two mime shows. I knew of nothing that could explain it. The issue must still have been on my mind when I listened to Randi’s lecture, because when it was over, I sat down and wrote him a letter. In the letter, I described what had happened and asked Randi how he would account for it. Is it possible, I asked, that people might emit some sort of vibrations or emanations, that these emanations might acquire strength in numbers, and that that’s what I was feeling when I stood there in the dark? As a performer, had he ever experienced something similar?

Randi wrote back — a bit brusquely, on a postcard — that the idea of emanations was nonsense. Whatever I was perceiving must have come to me in a perfectly conventional way, through my senses. Perhaps it was audience members’ body language, dimly visible in the dark. Perhaps there was something audible — the sound of audience members breathing, or shifting in their seats, or shuffling their feet on the floor — that communicated their feelings. Perhaps it was nothing at all — just my own state of mind that I was projecting onto the audience. In any case, there was no reason to resort to unscientific speculation.

Reading his reply, I felt both disappointed and embarrassed. I don’t know what else I could have been expecting. “Of course he’s right,” I said to myself. But a large part of me remained unsatisfied. Randi’s reasonable explanations failed to account for the strength, the palpability, the utter realness of what I had felt on that stage.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that a sensitivity to atmosphere had long been a part of my life. Even as a teenager, when I was fortunate enough to visit several old European cities, I was hesitant to walk into the awe-inspiring churches and cathedrals that were a standard part of the tour. There were always people worshipping inside — sometimes as part of an organized service, sometimes in private meditation — and I had the strong sensation that merely by entering the building, even if I stood quietly in the rear, I’d be interfering with their worship. My mere presence there as a tourist and a nonbeliever would pollute the atmosphere. I went inside anyway, trying to remain as invisible as possible, but nevertheless feeling that with every footstep and every breath, I was destroying something delicate and precious.

(To be continued in part 3)

I believe in emanations. I think there are all sorts of things happening that we don’t understand or that haven’t been catalogued or tracked yet. For example, birds can navigate by detecting magnetic fields that most humans don’t perceive – although I had a friend who could always find true north without a compass. He said that he could feel where it was.

I believe in emanations too, but investigators such as Randi would say that unless those beliefs can be supported by scientific evidence, then you and I are deluded. (I assume that your example of birds and magnetic fields has been scientifically validated, which puts it in a different category.)