(part three of four)

I once knew a woman who had grown up in a nonreligious family, and who remained an atheist into adulthood. Then, when she was about 30, some combination of circumstances brought her to visit an Eastern Orthodox church. In the church, she saw a painted icon whose eyes dripped tears of fragrant oil. She was incredibly moved by this experience. She returned to the church, soaked up some of the oil in a wad of cotton, and kept it in a small glass jar. Eventually, she converted to the Eastern Orthodox faith.

I found this chain of events incomprehensible. I had always known her as an intelligent, sensible person. Surely, I said to her, there was some earthly cause, some scientific explanation, for the icon’s tears.

“You weren’t there,” she said simply. Naturally, she said, her first thought had been that this was some sort of trick. But she could find no physical source for the tears, and no way they could have passed through the eyes of the icon. More important, there was evidently something undetectable by the senses — something in the atmosphere of that church — that penetrated deep inside of her and was able to overcome her lifelong habits of mind. For her, there was no question that this weeping icon was a miracle, a tangible sign of God’s presence.

I like to think that if I were there, I could have figured out (or at least devised a reasonable hypothesis for) what was making the icon cry. But as she said, I wasn’t there. And in the absence of independent evidence, who am I to doubt the reality of what she experienced?

After all, the way each one of us looks at the world is determined by our own experience. If I prefer to view the world rationally, it’s because experience has taught me that rational thought leads to answers that I find satisfactory. But there’s no proof of the rightness of rationality, other than that it feels right. The most elementary rules of logic — that a thing must either be A or not A; if A equals B, then B equals A; and so forth — are not provable. We believe them, and build our whole scientific worldview on top of them, because they appear self-evident.

Yet if there’s something in us that recognizes the truth of these logical axioms, then why should we not trust that same internal arbiter when it recognizes truth in other places? Science can establish facts about the world, but those facts are not always sufficient to explain our experience. In our experience, there are certain things that feel unquestionably true — as undeniable as the fact that A equals A. When scientific facts and theories don’t support what feels undeniably true to us, it’s reasonable to seek alternative explanations.

I’ve met several people over the years who claimed to have psychic ability of one kind or another. None of them earned a living as a mind-reader or fortune-teller; I saw no evidence that they were engaging in intentional fraud. So far as I could tell, they genuinely believed that they had the ability to read people’s thoughts, predict the future, or do something similar. In their experience, enough people had responded positively — “Why, yes, that’s true! How could you possibly have known that?” — that they had come to accept their talents as a fact.

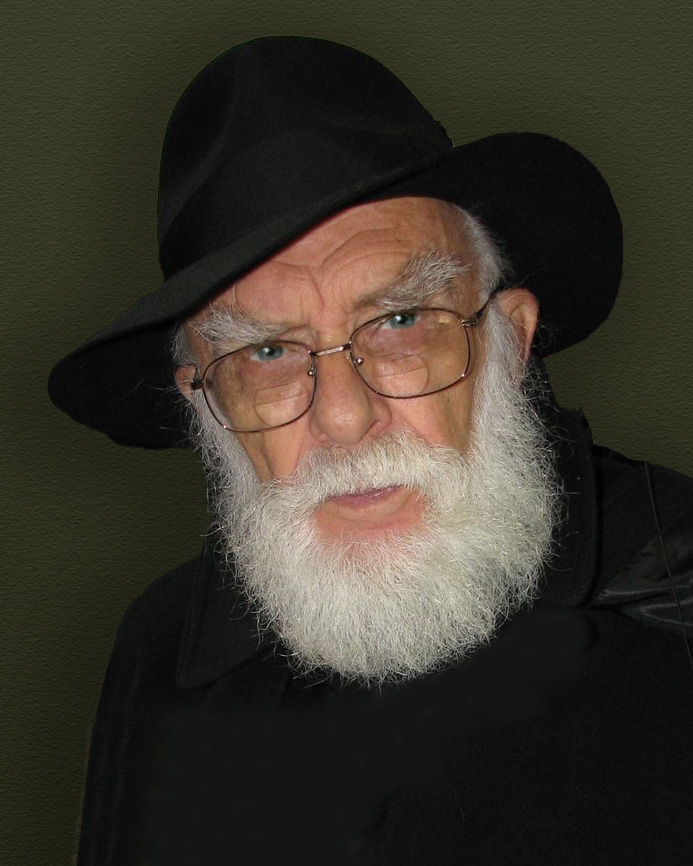

I’m sure an investigator such as the late James Randi would have no reason to doubt these psychics’ sincerity, or to claim that their successful readings hadn’t occurred. He would suggest only that they’ve interpreted their experience selectively — that they tend to remember the instances in which they were right, and tend to forget (or explain away) the instances in which they were wrong.

I once heard Randi tell a story which, as I remember it, went like this: A woman claimed that she had the power to find buried or hidden gold. Randi asked her how reliable this power was, and the woman replied, “It always works, 100 percent of the time.” As a first step toward testing the woman’s claim, Randi set out five wooden boxes, one of which had a piece of gold in it, and then asked the woman to pick out the box that held the gold. The woman chose the wrong box.

“Didn’t you say you’re successful 100 percent of the time?” said Randi.

“When I have the power,” replied the woman, “it works 100 percent of the time. I guess today I didn’t have the power.”

In defining their abilities such that their claims couldn’t be proven false, Randi said, people like this woman were refusing to play by the rules of science. Their rejection of the scientific method could mean only two things: either they were out-and-out frauds, trying to outsmart him and his fellow investigators; or they were sadly ignorant.

I’m not convinced that those are the only two possibilities. Living as I do in California, I meet people who claim matter-of-factly to have done a variety of extraordinary things: they have left their bodies, traveled to past lives via hypnosis, channeled the spirits of deceased people, or communicated with spirit guides. I would once have considered them flakes or crackpots. (Sometimes, of course, I still do, if I feel they’ve lost their capacity for critical thinking and intellectual inquiry.) But over the years, I’ve encouraged myself to avoid this kind of peremptory dismissal.

After all, these people have had experiences that I haven’t had. I might want to interpret their experiences differently than they do, but I don’t have sufficient information for that: As my Eastern Orthodox friend said, “You weren’t there.” (And even if I had been there, it wouldn’t have made much difference, since most of the relevant information lies out of my reach, inside the experiencer’s body and mind.) So rather than dismiss the people who tell me such stories, I try to embrace their experiences. And sometimes I even learn from them.

(To be continued in part 4)

Recent Comments