I’ve never liked it when, in the course of working through a disagreement, someone says to me, “I understand what you’re saying, but I don’t agree.” I find that irritating. “Clearly you don’t understand,” I want to respond, “because if you really understood, you would recognize the obvious truth of what I’m saying.”

That’s just an emotional reaction, of course. I can’t really object when someone claims to understand but disagree, because I find it equally irritating when someone assumes that my disagreeing with them is the result of ignorance or laziness. I once had an English teacher who loved literature, and if I read one of his favorite books and didn’t fall in love with it, he would insist that I hadn’t read the book closely enough. Or there’s the common retort from anyone who disagrees with me on social media — “Educate yourself!” — meaning that if I knew the same facts that this person did, I would automatically have to take their side.

The problem in all of these cases is that arguments are not based solely on facts. Any convincing argument has to start from a set of premises — statements that both the person making the case and the person listening assume to be true. Philosophers consider a valid argument to be one in which the conclusion follows logically from the premises, and a sound argument to be one in which the premises are demonstrably true. The traditional example taught in philosophy classes is:

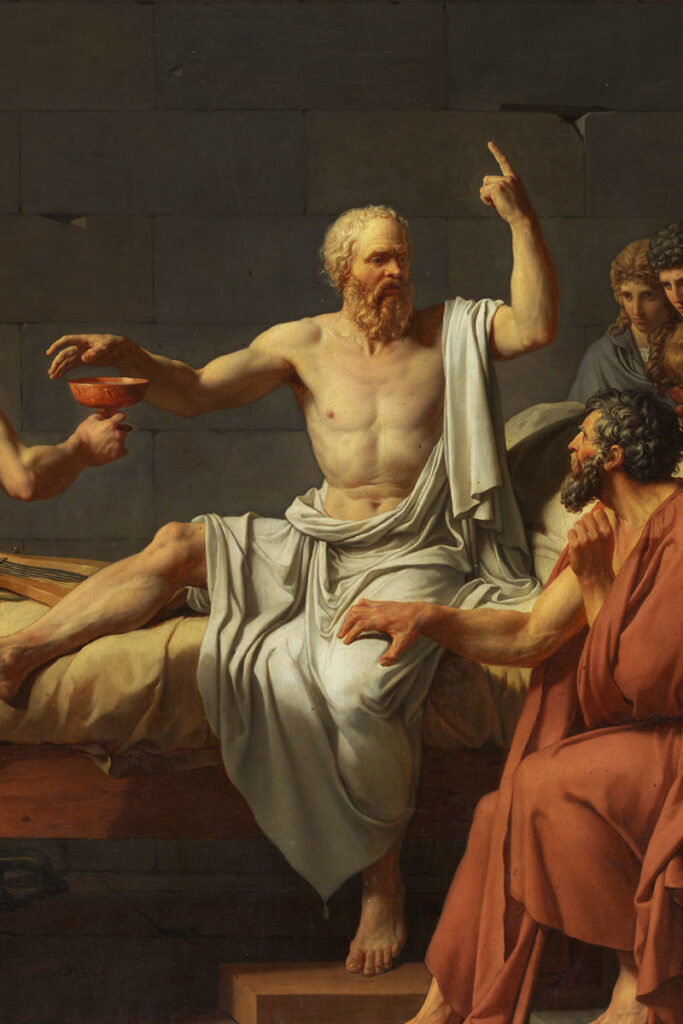

All men are mortal.

Socrates is a man.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

This argument is both valid and sound. Since both premises are indisputable facts, you have no choice but to accept the conclusion. (If you don’t accept the premise that all men are mortal, I would be perfectly justified — if a bit rude — in telling you to “educate yourself!”)

What complicates the matter is that premises don’t necessarily have to take the form of facts. In many cases, premises are values, and values can’t be held to a standard of truth. Let’s say I make this argument:

All lying is immoral.

Socrates has lied.

Therefore, Socrates has done something immoral.

“All lying is immoral” is not a fact; it is a belief. If you and I both hold that belief, then we can agree with the conclusion of the argument. But if you don’t believe that all lying is immoral, there’s no point in my telling you to go out and learn the facts. In your eyes, my argument is valid but not sound. The best either of us can say to the other is, “I understand what you’re saying, but I disagree.”

Serious conflict occurs when something that I consider to be a value is something that you consider to be a fact. For example, let’s say you make this argument:

Interfering with the process of human reproduction is immoral.

Using contraceptives interferes with the process of human reproduction.

Therefore, using contraceptives is immoral.

I might say, “I can’t accept your conclusion, because I don’t believe that interfering with human reproduction is immoral.” And you might reply, “It’s not a belief. It’s simply true.” And if you were in an arrogant state of mind, you might add, “Educate yourself!” Unfortunately, no amount of education is going to persuade me to accept your premise, because values are not provable; and each of us is going to resent the other for questioning our integrity.

I could end with the simple conclusion that telling people to educate themselves is not a constructive contribution to public discourse. But I’m driven to go a step further, and ask: If values and beliefs aren’t facts, how do people come to treat them that way?

I’m always fascinated with people who have strong religious faith. When I ask them why, they’ll say that it’s how they were brought up, or that it’s part of their culture. The question I always want to ask, but avoid asking for fear of being rude, is, “OK, you grew up among people who held these beliefs. But what led you, personally, to accept them?” I was given a full religious indoctrination when I was growing up, and yet none of it stuck, because no one could demonstrate to me that any of it was true. What causes some people to treat God as a fact, and others to consider God an invention?

It’s not a matter of education, because I know highly educated people in both camps. Religious or not, every one of us holds a set of values that we take to be self-evident. If I say, “Hurting people unnecessarily is wrong,” I don’t feel like I’m expressing a belief; I feel like I’m stating a universal truth. Yet that value isn’t any more provable than God is. If you were to ask me why a statement like that feels like so much more than a simple opinion, I really couldn’t give you an answer.

Recent Comments