Our household recently had a dinner-table conversation about the so-called Mandela effect, which refers to the sharing of a vivid — but false — memory by a large group of people. It gets its name from the many Baby Boomers who (it is said) have a distinct memory of Nelson Mandela’s dying in prison in the 1980s, when in fact he lived well into the 21st century. Other frequently cited examples are people’s remembering the children’s-book character Curious George as having a tail, or the “Mr. Moneybags” character in the Monopoly game as sporting a monocle. (As it turns out, neither is true.)

If you read my post “Fair Minded,” you know that I acknowledge the existence of invented memories, having experienced them myself. But when it comes to the Mandela effect, I’m skeptical of the idea that there are false memories that are culturally shared. For one thing, I’d assume that anyone who can recognize Nelson Mandela’s name would have noticed that he served as the first post-apartheid president of South Africa. (In passing, I should add that I’m irritated at how Mandela’s name has been trivialized by being connected to a piece of pop psychology.)

I’d also claim that most of the so-called false memories that are offered as examples aren’t memories at all, but simply mental images that get formed when the topic arises. For example, if you were to ask me, “Does Curious George have a tail?” I would probably think to myself, “Well, he’s a monkey, so I assume he has a tail,” and then I would immediately picture him that way. But that’s different from actually remembering him as having a tail.

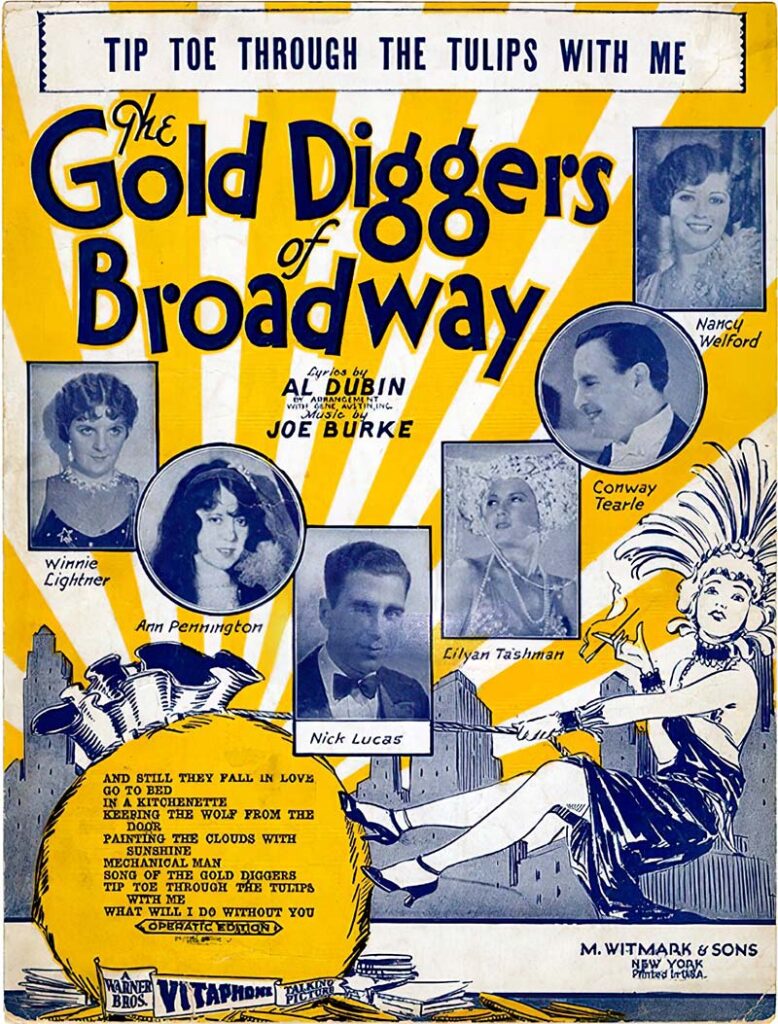

That said, I just came across what appeared to be an instance of the Mandela effect. While browsing around YouTube, I discovered some clips from a 1929 Technicolor musical called “Gold Diggers of Broadway.” Most of the film has been lost, but a few fragments survive, one of which features a tenor named Nick Lucas singing the (then-new) song “Tiptoe Through the Tulips.” Lucas’s rendition of the song was pretty straightforward, until he got to the bridge — the part that starts with “Knee deep in flowers we’ll stray.” It sounded odd at first, and when he got to the next line, “We’ll keep the showers away,” it just sounded wrong. The rhythm was off. At first I thought that the film editor had accidentally cut in an extra few beats, but no — when the chorus joined in, they sang it the same way. I was perturbed: This is not how the song is supposed to go.

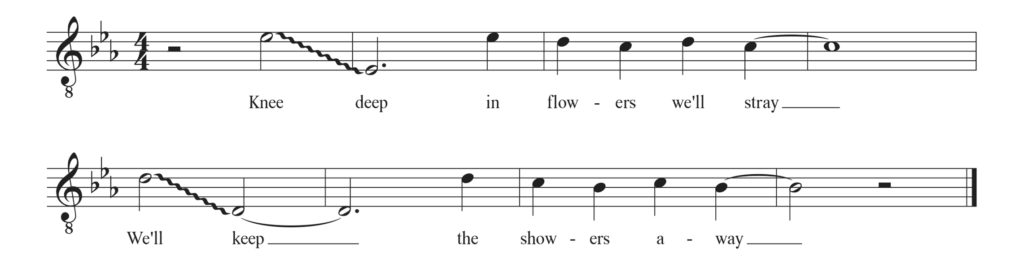

In my memory, the bridge went like this:

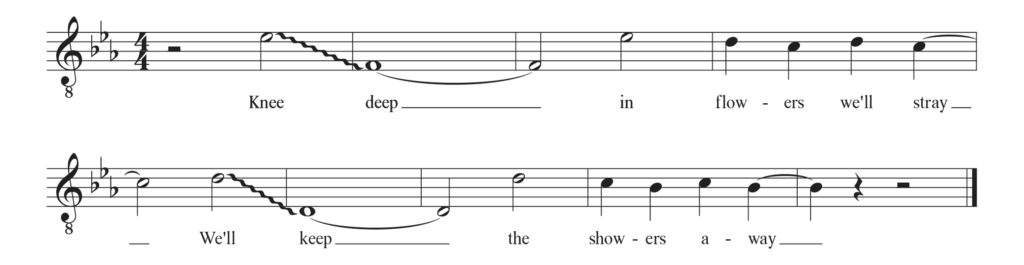

But in the film, it went this way:

Notice not only the difference in rhythm, but also how “deep” goes down only a seventh instead of a full octave. I checked the original 1929 sheet music — which, fortunately, is accessible online — and evidently that’s the way the song was written. So why did I remember it differently? And why did all of the cover versions on YouTube sing it my way instead of Nick Lucas’s way?

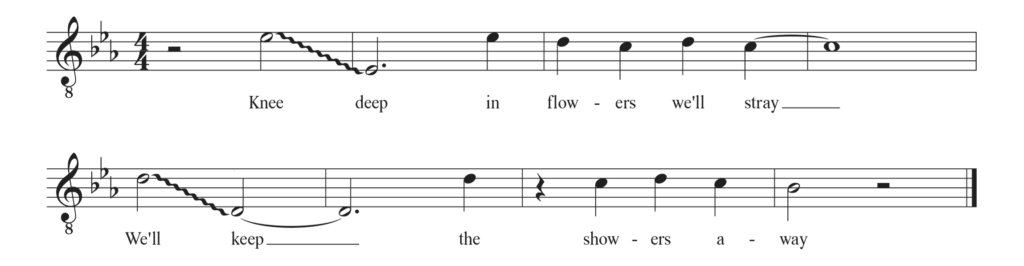

I was ready to attribute all this to a Mandelaesque mass delusion when I realized that I’d forgotten one important thing: When I and others of my generation learned the song, we didn’t learn it from “Gold Diggers of Broadway” — we learned it from Herbert Khaury, aka Tiny Tim. And as I discovered when I checked his classic 1968 recording, Tiny Tim sang it like this (which, apart from a syncopated flourish at the end, is just the way I remembered it):

Tiny Tim was an avid music historian, and he actually knew Nick Lucas — he insisted that Johnny Carson book Lucas on the infamous show in which he married Miss Vicki — so it’s not clear why he felt the need to alter the bridge from the way the song was originally sung. In any case, it’s clear that the Mandela effect doesn’t apply here. I don’t have a false memory of how the song went in 1929; I have a true memory of how the song has gone since 1968.

Recent Comments