I was in third grade, and had just taken a spelling test. I’ve always been a good speller, so I knew I’d aced the test. But when my paper came back, I was startled to see one of my answers with a big red X next to it.

“Why did you mark this wrong?” I asked the teacher.

“Because you wrote gray or grey,” she replied.

“I wanted to be complete,” I said.

“This is a test!” she said. “You can’t give me a choice between two different answers. You have to give a single answer.”

“But they’re both right,” I said.

“I don’t care,” she said. “You have to choose one or the other.”

I was getting frustrated. “How do I pick one or the other when they’re both equally right?”

“Just pick one,” she said.

“But…”

“I’m tired of arguing with you,” she said.

“G-r-a-y,” I said, defeated.

“Correct,” she said, although it was less correct than the answer I’d originally given.

This was my initiation into the world of “you can’t say that,” in which — due to unwritten rules, norms, or business considerations — saying something that you know to be true is not allowed. I’m sure we’ve all encountered such situations. Here are a couple that stand out in my memory.

A client of the publishing company I worked for was thinking of using a new technology to create some interactive learning materials. As a young project director, I was charged with doing a feasibility study to find out whether their idea was practical. After doing extensive research, I concluded that what they were proposing was unlikely to work, and I wrote a report saying so.

“The report is fine,” said my boss, “but you have to change the conclusion.”

“What do you mean?” I said. “All of the evidence I cite in the report suggests that their idea is impractical.”

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “If we say that their idea isn’t practical, they won’t hire us to develop the prototypes.”

“But the prototypes won’t work,” I said. “Besides, as the person who did the research and wrote the report, don’t I get to decide what the conclusion is?”

“Where did you get that idea?” he said.

For days afterward, I heard him telling my more experienced coworkers, “Mark thinks that just because he wrote the report, he gets to decide the conclusion!” And they would all laugh.

Starting around 2005, community colleges like the one I taught at were forced to adopt an assessment paradigm called Student Learning Outcomes, or SLOs. The point was to hold colleges accountable for their educational effectiveness by offering quantitative evidence that our students were actually learning what we claimed to be teaching.

I could understand the desire for accountability, but the idea of quantifying students’ learning in creativity-centered classes made no sense to me. Unlike in math or science, the quality of students’ imaginative work can’t be measured in any objective way. My students tended to be of a range of ages and backgrounds, and each enrolled in the course wanting to get something different out of it, so I couldn’t imagine any consistent scale that would apply to all of them. And finally, if my own experience is any guide, most of the best lessons that teachers impart don’t have immediate results — they incubate in a student’s brain and may not have any observable outcome until years later.

At the end of each semester, we were required to file an SLO report in which we would give a quantitative measure of each student’s learning, compare that to a numeric goal that we had previously set, and describe what changes we planned to make based on the difference between the two. I managed to come up with a number that represented each student’s learning, but the goal I specified was always 0. As for the changes we planned to make, I always wrote the same thing: “The measurements in this report are arbitrary and meaningless, and therefore I don’t plan to make any changes based on them.”

I did that for years, and no administrator ever complained — chiefly, I think, because nobody actually read my submissions. Then, one day, I had a visit from a representative of the Student Learning Outcomes Assessment Committee, who asked, in effect, what the hell I thought I was doing.

“Everything I wrote is true,” I said. “The data are meaningless.”

“I don’t care if it’s true,” he said. “You can’t say that in the reports.”

“Nobody has complained up until now,” I said.

“Our accreditation is up for renewal,” he reminded me. “The committee from the ACCJC [the Accrediting Commission of Community and Junior Colleges] will be coming here to examine all of our records. They’re expecting to see 100 percent SLO compliance. Based on what you’ve written, they could put us on warning.”

“But I haven’t technically violated the rules,” I said.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “You have to play the game.”

Playing the game required me to rewrite six years of SLO reports. The revised reports, of course, had no more value than the original ones; they were just longer and contained the right words.

What can we conclude from stories like these? We’re taught as children always to be honest; then, as adults, we’re required not to be. And the examples I gave here take place only in the business world. There are many instances of “you can’t say that” in our personal lives, as well.

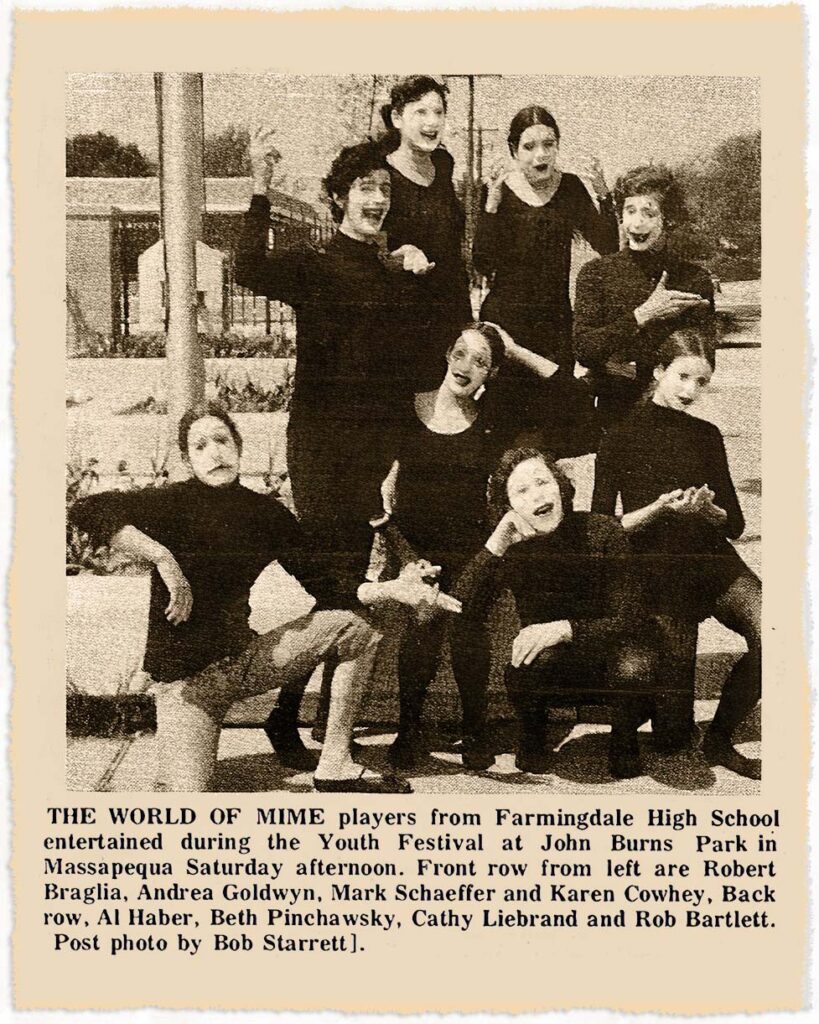

Sometime in my 20s, I got a phone call from an old friend — someone I’d known since childhood and had become buddies with in high school — inviting me to his annual Halloween party. I’d been to his Halloween parties before, and I’d never had a good time. They consisted of some strained conversation among people who were as socially awkward as I was, followed by a showing of some horror movie on video. I’d gone every year out of loyalty to him, but I just didn’t feel like it this time.

“You know I value your friendship,” I said. “We’ve known each other for a long time, and I wouldn’t feel right lying to you. Driving from New Jersey to Brooklyn is a long way to go, and it doesn’t feel worth it to me. The truth is, I don’t really enjoy your Halloween parties that much.”

There was a long silence on the other end of the line. I waited, hoping that he would respect and appreciate my honesty.

“You know,” he finally said in a hurt and angry voice, “you could have just said that you were busy.”

Recent Comments