Despite my complete lack of interest in sports, social circumstances have required me, every ten years or so, to attend a major-league baseball game. This isn’t as horrible as it sounds, because — thanks to my dad dragging me to Mets games when I was a kid — I at least understand the rules of baseball. Football by contrast, is a complete mystery to me. It appears to consist almost entirely of men piling on top of each other, with the piles occasionally migrating toward one goalpost or the other.

As frequent commenter John Ozment has pointed out, unfamiliarity with the game was a liability in childhood phys ed classes. The gym teacher would never explain how to play football; it was just assumed that everybody knew. We were just told to go out on the field — shirts vs. skins — and play it.

Even if I’d had some insight into the game, I completely lacked the skills to do anything about it, so I was generally assigned to the position of linebacker. My teammates would patiently show me how to fold my arms in front of me, and then explain that the players from the other team were going to run toward me, and that my job was to keep them from getting through the line. That, of course, was a crazy idea. It was clear to me that if a determined, physically fit body was charging at me, there was no possible way I could impede its progress. So when said body was in fact hurtling toward me, I did the sensible thing and stepped out of the way. I have no memory of what sorts of things would happen after that, although I assume that they involved people piling on top of one another.

Baseball is a different story. Although I lack the ability to throw, catch, or hit a ball, I at least understand what it means when other people do it. So when I make my decennial visits to a major-league ballpark, I’m at least theoretically equipped to cheer and hiss at the appropriate times. What I wasn’t prepared for was the crowd’s behavior at my most recent Oakland A’s game. (This was well over ten years ago — I’m long overdue for my next baseball experience.) When the members of the opposing team made their entrances, each introduced by name, the Oakland fans booed them. Not because of anything they’d done — the game hadn’t started yet — but simply because they belonged to a rival team.

I was appalled, as I explained to a friend later. “I thought baseball was supposed to be about good sportsmanship!” I said. “Aren’t the players on the other team professionals, deserving of respect? And when people from somewhere else visit your city, aren’t you supposed to make them feel welcome?” My friend looked at me as if I were a space alien in a human-skin suit.

But it used to be about good sportsmanship, didn’t it? I don’t remember any Mets fans booing the teams who visited Shea Stadium in the 1960s. For that matter, I don’t remember such a thing happening when I made my first visit to the Oakland Coliseum thirty-something years ago. The only explanation I can think of is that baseball players didn’t make as much money back then, so maybe there was more of a sense that they were people like us, who could be our friends or neighbors.

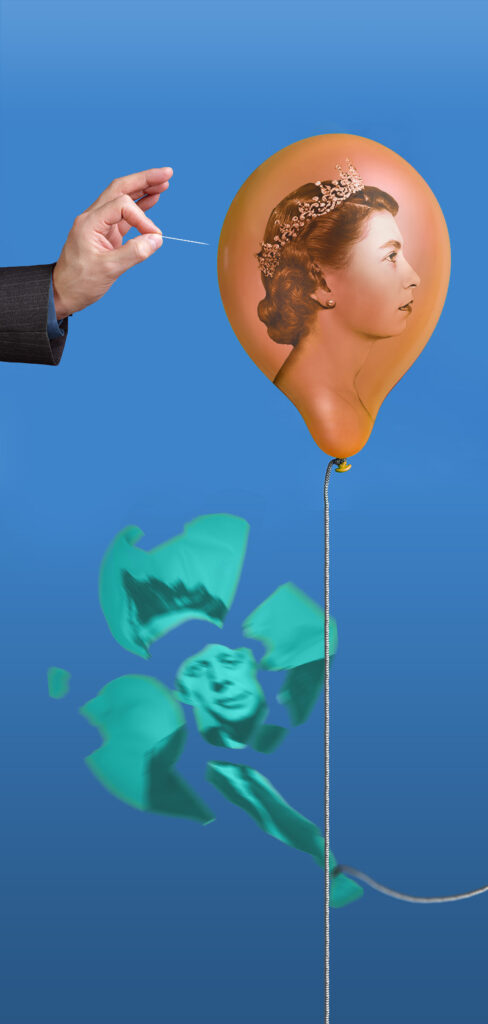

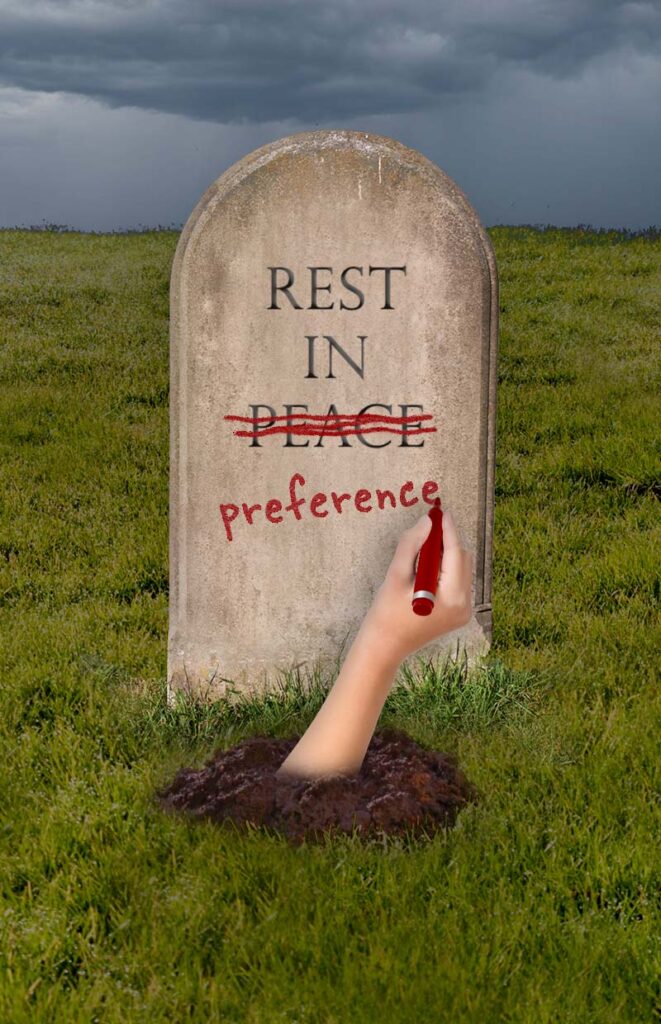

This is all brought to mind by an article I recently read in the New Yorker about a game called pickleball, which I’d heard of but knew nothing about. According to the article, pickleball started as a tennis-like game that anyone — children, adults, senior citizens in retirement communities — could play and win, even in combination with each other. It was suffused with good humor and community spirit. But in recent years, pickleball has become professionalized, with official leagues and big-money contracts. There’s a growing gap — not just in skill level, but in attitude — between the professionals and the amateurs, and between members of the two national leagues. Pickleball isn’t just for fun anymore; it’s serious.

Is this sort of devolution inevitable? Outside of the sports world, the closest analogue I can think of is the World Wide Web. The invention of the website and the browser brought the internet — previously reserved for nerds and academics — to everyone. The online world was a shared space, where anyone from goofy kids to specialized scholars could set up a site, and where everyone’s site was equally available to visit. A good website back then was considered to be one that had lots of links, giving the reader plenty of opportunities to encounter things they never would have come across otherwise. (The expression “web surfing,” now considered quaint, referred to the addictive practice of jumping around the web from one site to another, following wherever the ever-inviting links led you.)

That vision of the internet is gone. Sometime around the turn of the century, the model of a good website was no longer one with lots of jumping-off points, but one that was “sticky” — one that kept the visitor on your own site for as long as possible. How else could you make money? Sharing was out; ads (measured by eyeballs) and paywalls were in. Anyone who didn’t have a plan to monetize their site couldn’t be taken seriously. (That awful word “monetize” originally meant to convert something into money, as in creating a currency; the present meaning of “turning something free into something that earns a profit” is entirely a recent invention.)

The one thing that all of these examples have in common is the corrupting influence of money. As much as I hated phys ed classes, I can appreciate that they weren’t intended to train us for careers as professional athletes; they were just about play for its own sake.

Recent Comments