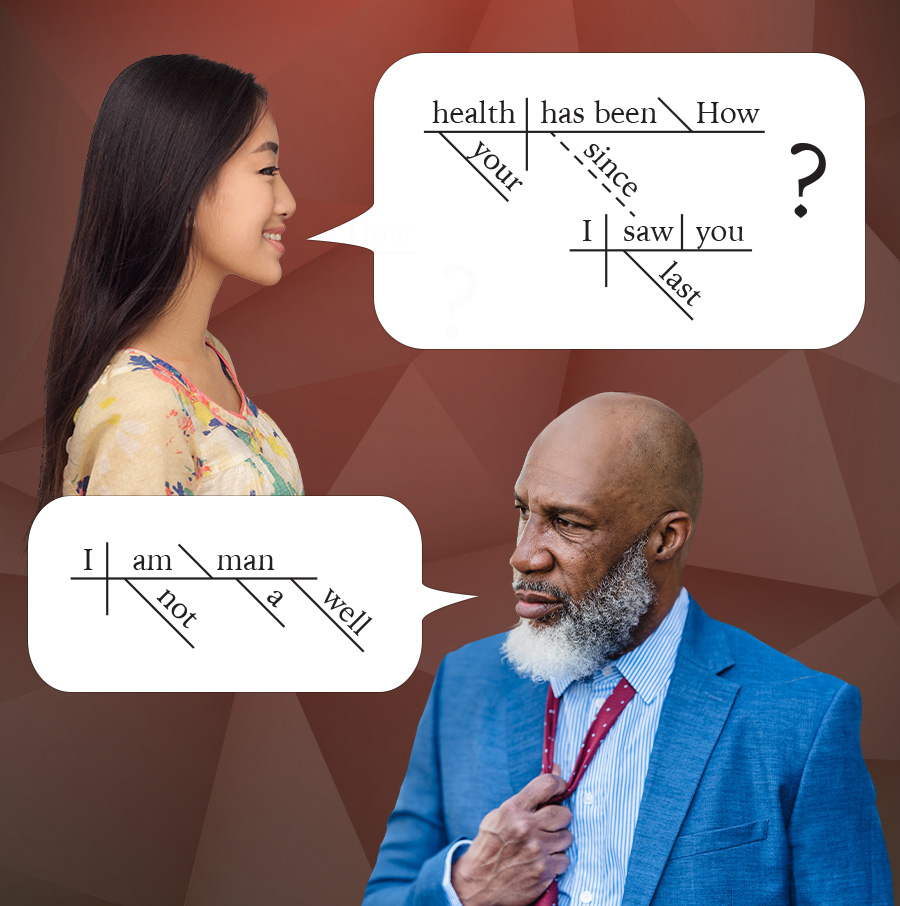

My wife Debra and I were at a recent social gathering where a friend remarked that he “felt badly” about something. Then he immediately stopped. “Wait,” he said. “Should that be ‘felt bad’ instead of ‘felt badly’?”

“It’s ‘felt bad,’ ” Debra said. “‘Felt badly’ means that you weren’t very good at the act of feeling.”

“But ‘felt’ is a verb,” someone said, “and so you have to use an adverb. And ‘badly’ is an adverb, right?”

“Yes,” said I, unable to contain myself. “But ‘to feel’ is a copulative verb.”

Given that this was a well-educated group, most of whom worked with language professionally, I guess I expected their response to be something along the lines of, “Ah, yes, of course.” But instead, all heads turned toward me incredulously. “A what?” said at least one person.

“A copulative verb,” I said. “A verb like ‘to be’ or ‘to appear.’ It takes an adjective rather than an adverb.”

“But what about ‘I feel well’?” said the original speaker. “ ‘Well’ is an adverb, isn’t it?”

“Sure,” I said, “but it can also be an adjective — as in ‘I’m not a well man.’ When you say ‘I feel well,’ you’re using it as an adjective.”

I shouldn’t be surprised at the general unawareness of copulative verbs. They’re not the kind of thing that come up in everyday conversation. (Some Googling revealed they’re now more commonly called “copular” verbs, presumably because it sounds less dirty.) I’m sure that I would never have heard of them, except that the concept was drilled into me when I was in fourth grade.

Yes, fourth grade! I’ll grant that I didn’t have a typical elementary school education, but for some reason my teacher was so convinced of the importance of copular verbs that she taught us a song about them (sung to the tune of “This Is the Way We Wash Our Clothes”):

Act and feel and get and grow,

Be, become, stay, and seem,

Look, sound, smell, and taste

Are all copulative verbs.

Apart from allowing me to show off at parties, I have to wonder: Is this bit of knowledge an efficient use of my rapidly diminishing brain cells? I loved studying grammar when I was a kid, especially when we started learning to diagram sentences (also in fourth grade). Being able to precisely parse the structure of a sentence allowed me to write with increasing confidence and authority, a skill that got me surprisingly far in life.

But how important is it, really? So far as I can tell, kids in the 21st century study very little grammar — not much beyond learning the difference between a noun and a verb — and yet their communication skills appear adequate for most purposes. After all, when we use language, we generally don’t follow a conscious set of rules; we speak or write instinctively, based on example and habit. Even if no one at the aforementioned social gathering was familiar with the concept of copular verbs, they still most likely say “She looks young” rather than “She looks youngly.”

Knowing the rules can help when questions come up, but even those instances don’t seem to matter much. Smart, educated people can say “I feel badly” — and often do —without anyone questioning their intelligence or level of education. I’ve come to feel that the finer points of grammar are just something for language nerds to amuse themselves by, just as baseball fans argue about batting averages and RBIs. It’s a harmless activity, but it’s not going to contribute much to the progress of civilization.

Recent Comments