I wish I could remember how my family ended up in this nearly-empty restaurant one rainy night. Maybe we were coming back from a long car trip, and we were hungry and cranky, and my father pulled off the road at the first restaurant that looked family-friendly. The restaurant was attached to a shabby motel, and we had to walk through a hallway to get into it. Just before we turned the corner, I sensed something strange on my right. I glanced over and saw a plain wooden door with glued-on plastic letters that spelled out MELTING ROOM B.

I couldn’t concentrate on my meal. All I could think about was what could possibly be behind that door. What would a motel need to melt? And why would it need not one, but two or more rooms to do it in? Were the motel guests using or consuming something that came from the melting room? Was I? Did my school have melting rooms too, and I’d just never noticed them?

My questions became moot when, on our way out of the restaurant, I noticed another door with the same type of glued-on plastic letters. It said MEETING ROOM A.

As satisfying as it was to have the mystery solved, I was disappointed to have the melting room taken away from me. The thought of it had been tantalizing, as if something from a horror movie had suddenly appeared in the real world, and I was the hero who discovered that something isn’t right.

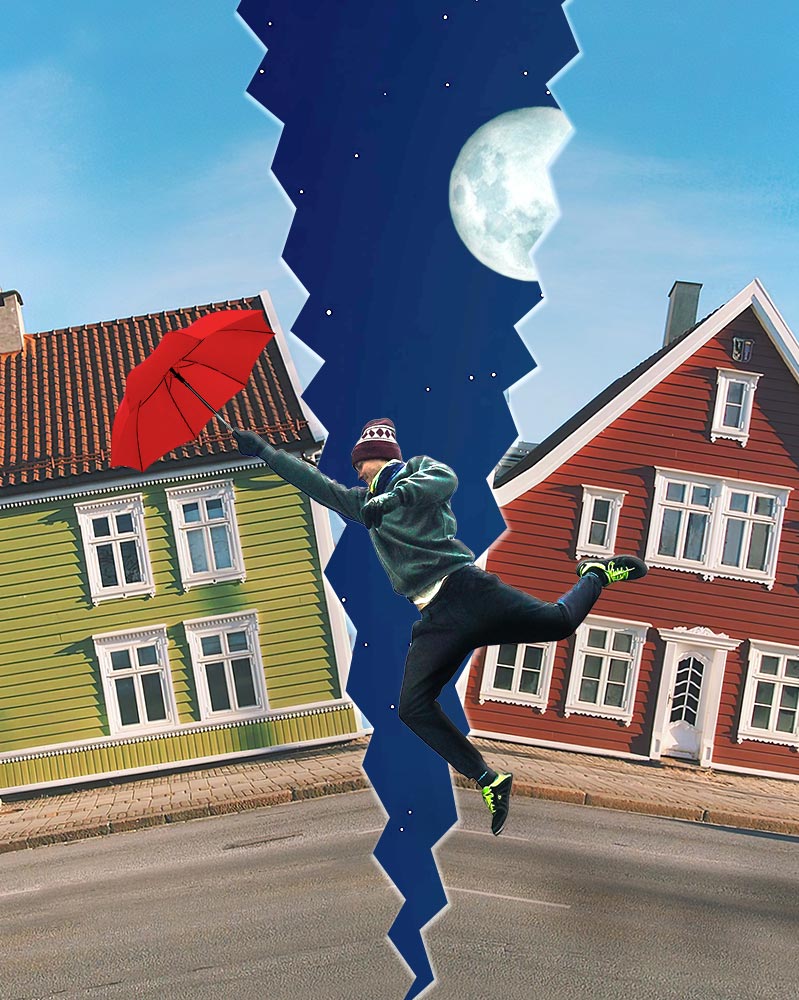

In fact, the melting room never really went away — it still exists in the parallel universe of my imagination. I wonder whether other people have a personal world populated by people and things that seem to have some kind of existence, even if not a physical one.

My parallel universe grew larger when I entered college. Each of us was given a book called the Freshman Herald, filled with head shots, hometowns, and birthdates of everyone in the incoming class. (This was back when “facebook” really meant a book with faces in it.) Like many other lonely first-year students, I leafed through the book often, looking at the people I might encounter and forming impressions of who they were. One face stuck with me in particular: a young woman with honest eyes and a kind smile, her head at an inviting tilt, her hair illuminated by sunlight falling through leaves. The fact of her being somewhere on campus made me feel all warm inside. I hoped that I would someday find out how it felt to be in her presence.

As it turned out, I didn’t meet her until two or three years later. She was a perfectly fine person — I liked her immediately — but she didn’t have the gentle aura and sincere smile of the girl in the picture. Her voice was wrong, her manner was wrong, her physical presence was wrong. Without the halo of sunlight, even her hair was wrong. I felt the same mix of emotions that I’d had on that night when I left the restaurant: relief that my curiosity was satisfied, but sadness that the person I’d been connecting with for so long was imaginary. In this case, it was more than sadness. It felt something like grief.

As with the melting room, though, I took solace in knowing that since the person in the photo had never really existed, she couldn’t be taken away. I still felt all warm inside when I looked at her picture. Even now, I think of her as two different people who happened to live in two different universes.

Living with this sort of cognitive dissonance becomes more complicated when morality enters the picture. Consider the case of Bill Cosby. I was seven years old when I first heard a recording of Cosby’s “Noah” routine, in which God informs Noah that he’s going to destroy the world, and that Noah therefore needs to build an ark. (Noah: “Right…. What’s an ark?”) I thought it was hilarious, especially given my already developing skepticism about religion.1 Although I never followed Cosby’s career very closely, I always enjoyed encountering him on TV — guest-hosting for Johnny Carson, repping Jello pudding, embodying the world’s most admirable father figure on “The Cosby Show” — and always felt like the world was a better place as a result of his being in it.

When it eventually came to light that he was, in fact, a despicable man with a long history of drugging and raping women, my warm feelings toward him naturally turned brutally cold. Yet the knowledge that Cosby was a monster can’t erase the many years in which I experienced him as a benign and genuinely funny presence. Is it OK that the benevolent Cosby still exists as a cherished inhabitant of one mental universe, while the vile Cosby casts his shadow over another? Can I still look back fondly on the brilliant early films of Woody Allen or the insightful comedy routines of Louis C.K. while acknowledging that those men never existed as I imagined them?

The universe where the melting room exists isn’t necessarily a better one. (The melting room itself remains pretty creepy.) And unlike the “real” universe, it will cease to exist when my life ends. But as long as I can still derive pleasure from visiting it, I have no wish to abandon it.

Recent Comments