Since most of my blog posts are not time-sensitive, dealing as they generally do with events that happened 40 or 50 years ago, I’ve never been in a hurry to make them public. Some of them were written weeks or even months before you see them, giving me time to rethink them and tweak them and sometimes even throw them away.

This is one of the rare posts that are written on the same day they are published. We’re in the UK, you see, and the queen is dead.

Debra and I arrived in London a week ago for a two-month stay. We settled into our basement flat in West Kensington and strolled over to North End Road, the nearby shopping street, to check out the neighborhood. I’m always self-conscious when I first arrive in a foreign country, feeling like everything I’m doing is wrong. Am I wearing the wrong clothing? Am I talking too loudly? Am I supposed to walk on the left side rather than the right? Suddenly an older woman stopped in the middle of the sidewalk and stared right at me. I was about to apologize for whatever I’d done wrong, when she gasped, “The Queen has died!”

I don’t know what one says in a situation like that. What I said was, “I’m sorry,” which is what you say when someone tells you that their grandmother has passed away. Hopefully my American accent made my response seem less inappropriate.

It’s not clear how the woman had gotten the news at that moment — was she in the middle of a phone call? — but clearly the queen’s death was not yet common knowledge. Debra and I looked at each other. “We’d better get some groceries, quick, before the news spreads and the whole city shuts down,” I said. We ran into a convenience store and bought a few prepackaged meals, then went next door and snagged some dinner from a fish-and-chips shop that was about to close. That was our first day in London.

As it turned out, the city did not shut down. I’m sure that plenty of people watched the 24-hour coverage on the BBC; many others gathered outside Buckingham Palace, despite the fact that no members of the royal family were inside. But life remained surprisingly normal in the subsequent days — the pubs and the theaters remained open, the stores engaged in business as usual, and young people continued to promenade along the south bank of the Thames.

It’s only when you talked to Britons — particularly older ones — that you found out the truth. Life was normal on the surface, but not so in people’s hearts. People told us that they felt cast adrift, that the world suddenly felt unreal. “I’m not especially in favor of the monarchy,” was a common comment, “but even so, she was a source of stability and continuity. She’s been the Queen all my life!” King Charles III feels like a barely adequate replacement.

I can’t help thinking of the afternoon of November 22, 1963, when John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Students were dismissed from school early, and I arrived home to find my mother in tears, sitting at the kitchen table surrounded by crumpled tissues. It’s difficult to imagine anyone today having such an emotional reaction to the death of a national leader, but the connection between Queen Elizabeth and her subjects seems to come close.

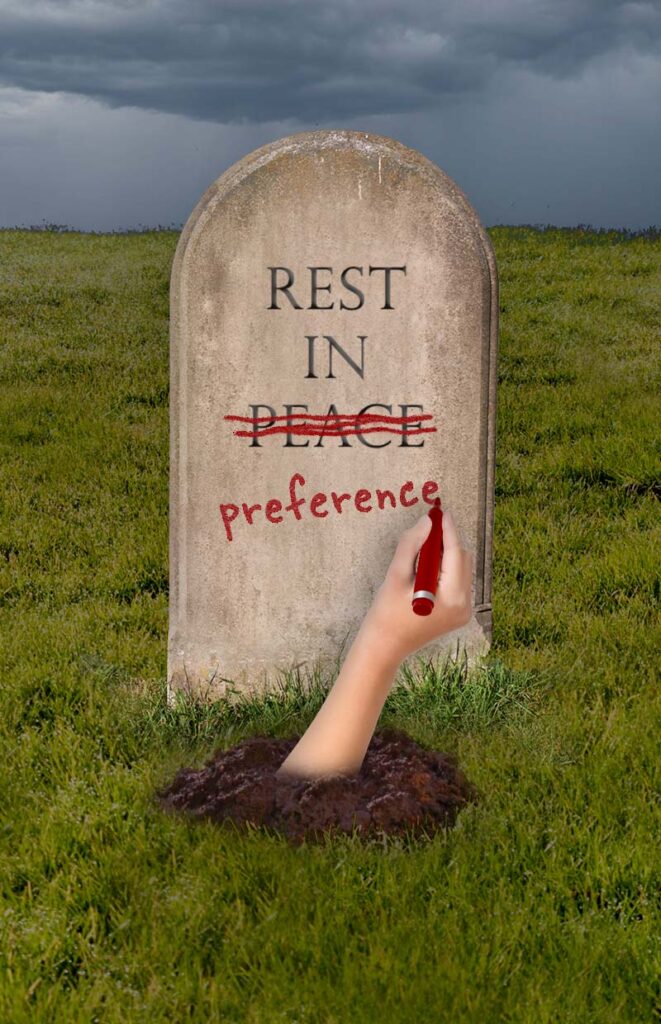

I don’t mean to equate the two events. JFK’s death was sudden, shocking, and horrifying, while the queen’s impending death has been anticipated for years. Her death was natural; his was not. But the one thing that both deaths seem to have in common is that for the citizens whose leader had been lost, the world never felt the same afterward.

In the case of Kennedy, America permanently lost its innocence — it was as if Adam and Eve had just eaten the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and suddenly realized that they were naked. JFK had been a symbol of youth, energy, and optimism, of the best times that were yet to come, and now that vision of the future was exposed as an illusion. Even though I was a child, that shock of recognition felt very real to me.

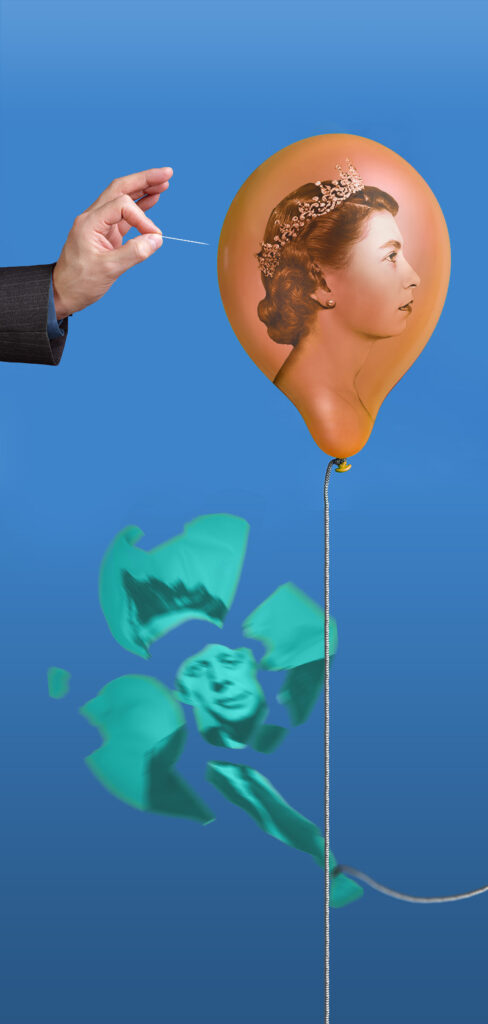

Queen Elizabeth, for her part, was the British people’s last connection to a long-mythologized past — a time when Britain was at the center of an empire and a leader of the world, a small but noble nation that stood bravely against the Nazis in World War II, a symbol of the superiority of Western civilization. That whitewashed characterization of the UK’s global role is no longer accepted intellectually, but it has always remained potent emotionally. With the queen’s passing, the last tether of the present to the past has given way.

The queen’s funeral is scheduled for next Monday, and on that day the city — and the country — really will shut down, as I remember happening in the United States during the funeral of JFK. Just as my eyes were glued to the small, flickering screen of our black-and-white TV in 1963, I’ll be watching the ceremony intently — albeit this time on a large, bright, flat screen in vivid color. The first broadcast was about the death of the future; the new one will be about the death of the past.

Recent Comments