The first new car my parents ever bought was a 1962 Rambler American. (Their previous car, acquired when they moved our family from the Bronx to the suburbs, had been a used ’56 Chevy.) The Rambler, despite being an “economy” model, was pretty up-to-date: It had a stylish, compact design, high (for the time) gas mileage, and an automatic transmission controlled by push buttons on the dashboard.

One thing it didn’t have, however, was seat belts. (The US government would not mandate seat belts in new cars until 1964.) My parents eventually had aftermarket seat belts installed — non-retractable lap belts that were inelegantly bolted to the floor. They also sprang for an aftermarket windshield washer, which the driver could operate by stepping on an air-filled rubber bulb. The total cost of the car, so far as I can determine now, was about $2,500 — equivalent to about $24,700 in today’s dollars.

The Rambler comes to mind because my wife and I have recently been shopping for a new car, which in our case is a Toyota Prius. The manufacturer’s suggested retail price for a 2022 Prius L Eco, the lowest trim level, is about $25,000, which is not that much higher than what my parents paid for their ’62 Rambler. Unlike the Rambler, however, the Prius comes equipped with power steering, power mirrors, anti-lock brakes, a digital “infotainment” system, driver and passenger airbags, air conditioning, cruise control, a back-up camera, lane-keeping assistance, a wifi hotspot, and (or course) a fuel-saving, environmentally friendly hybrid engine.

Debra and I elected to go with the next-higher trim level, the LE, which — for an extra $1,500 — gives us blind-spot monitoring, a cross-traffic alert, front and rear parking sensors, and parking assistance. (These were our chief reasons for wanting a new car in the first place, since we both have vision problems, and having additional safety features becomes all the more important as we age.)

What stands out for me is how high Americans’ expectations have risen for what a car is supposed to do. In 1962, a car was basically a box on wheels, a means for reliably getting from one place to another. Now, sixty years later, we expect a car to be an insulated, protected, immersive environment that not only transports us, but does as much as possible of the work for us. And yet, in constant dollars, the price of a car hasn’t really changed much.

In our various trips to Europe over the years, including our most recent one to the UK, we’ve visited a number of medieval castles and royal palaces. My reaction is always one of wonder at how far we’ve come: Most of us have a quality of life that’s safer, more comfortable, and more convenient than that of any historical lord or king. (Even in the case of going to the bathroom, I’d rather use a modern toilet than whatever Henry VIII had to sit on.) And the price of that comfort is vastly less than whatever it cost the rich and powerful to maintain their quality of life. I come away feeling fortunate and grateful.

Debra, interestingly, has a different reaction. She looks at the primitive conditions under which medieval royalty lived and recognizes that they, in their time, thought that they were living in the greatest possible comfort. People hundreds of years in the future, she says, will marvel at the crude conditions that we’re content to live under. In that context, we’re no better off than were the occupants of those dark and drafty castles.

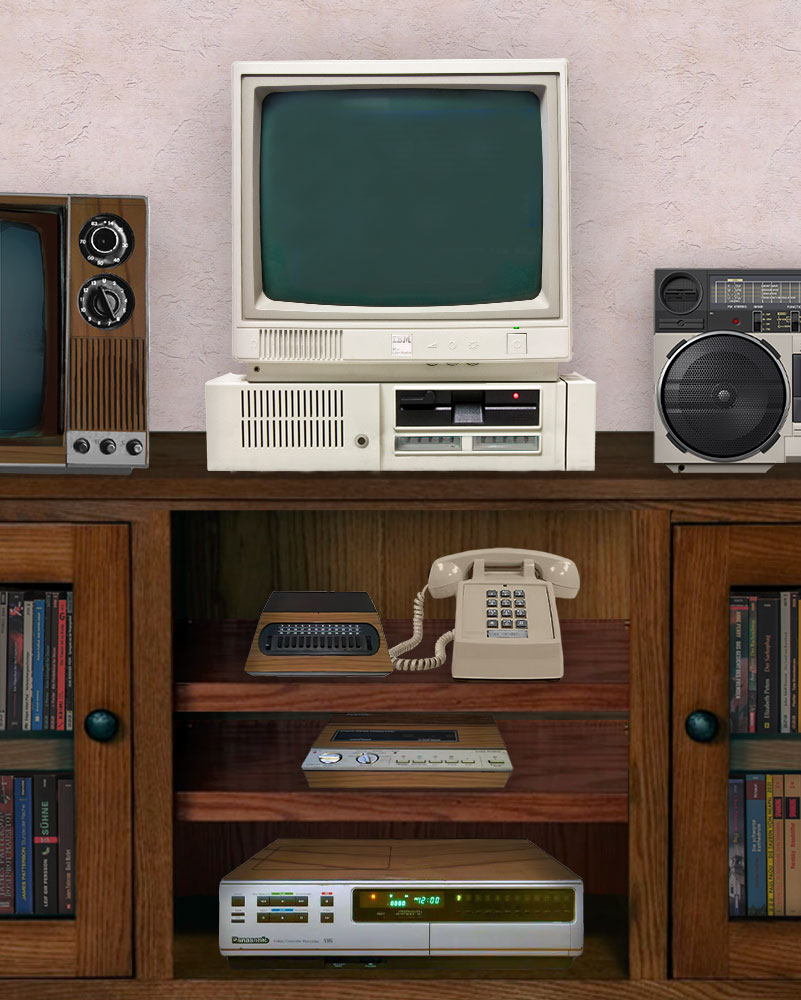

And I suppose she’s right. In 1962, the year my parents bought our new Rambler, they also bought our first solid-state TV, a portable model that didn’t need time to warm up. John Glenn orbited the earth for the first time, and NASA launched Telstar, the satellite that made international broadcasting possible. My mother abandoned her eyeglasses for contact lenses — tiny, curved pieces of hard plastic that you could put directly in your eye! A few years later, I got my first tape recorder, and my friend Carl’s family got a color TV. My uncle bought a Polaroid camera that made photos available instantly. The Ranger VII space probe radioed back the first closeup photos of the surface of the moon. My neighbor gave me his used transistor radio, not much larger than a pack of cigarettes.

I was still a child, but I was certain that there was no greater time to be alive. And at the time, there wasn’t.

Recent Comments