To introduce the theme of encounters with unfamiliar technology, my earlier post “Hi, Tech!” began with a famous scene from “Nanook of the North” in which the titular Nanook bites down on a phonograph record. I knew that the most appropriate illustration for the post would be a photo of that moment, so I downloaded a copy of the film — it’s in the public domain, so online copies are plentiful — and began to search, one by one, for the frame that would work best as a still image.

Frustratingly, none of the actual frames from the film matched the iconic picture that I had in my mind. There was one frame where the record was positioned just right, but Nanook’s body was twisted in an awkward position that made it difficult to make out what he was doing. There was another where Nanook’s body was positioned perfectly, but the record was reflecting light directly into the camera and therefore looked like a featureless, glowing disc. Furthermore, every frame that I looked at had compositional problems: Nanook’s head was partially cut off, or his fur-lined hood was indistinguishable from his hair, or the white pelts that covered his upper legs blended with the white background, making him appear legless. To my dismay, the perfect moment that existed in my memory didn’t exist in the film.

The image that I ended up posting is a composite of elements from four different frames. It took me hours to put together, which felt ironic because the actual filming of “Nanook of the North” was done on the fly, unrehearsed, as the director Robert Flaherty stood in the cold and wind and pointed his camera. None of the fleeting moments that he captured was ever meant to be examined as closely as I examined those individual frames, cutting them apart pixel by pixel.

As I worked, I couldn’t help but reflect on the miraculous process that allowed these nearly 100-year-old images to land on my computer screen. Out there in the Arctic tundra, sunlight reflected by Nanook and his companions passed through the lens of Flaherty’s hand-cranked camera and chemically altered the light-sensitive coating on a strip of film, creating a negative. Each night, Flaherty developed and printed the negative onsite in a primitive darkroom. (He always made sure to show the Inuit participants what he had shot the day before, thus encouraging their continued collaboration.) Eventually, the negative was carried back to the United States, edited, and brought to a laboratory, where it was used to create prints that went out to cinemas for public exhibition.

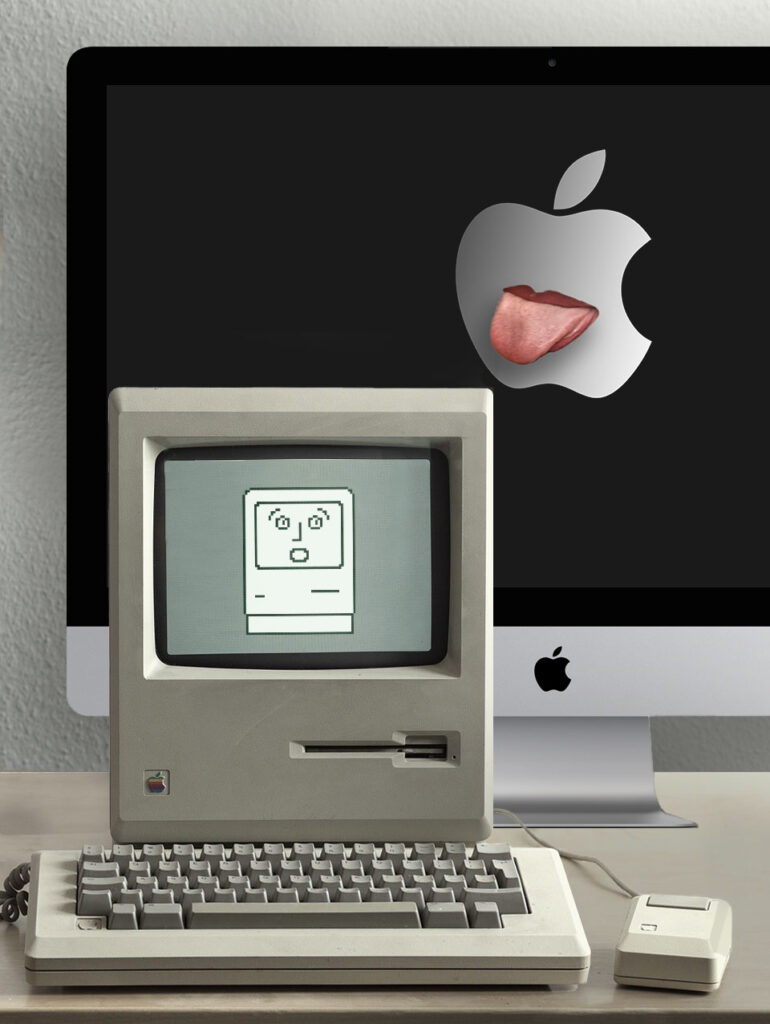

Over the years, people struck duplicate negatives from existing prints and made new prints (which, unfortunately, were of successively lesser quality with each new generation). At some point in our own century, somebody digitized one of those prints, converting the patterns of light and dark into a series of ones and zeroes, and uploaded that information to a worldwide network of computers. From there, it was downloaded to the hard drive of an iMac in a house in Oakland. And now those ones and zeroes were displayed by my computer as patterns of light and dark on its screen, essentially duplicating the patterns of reflected sunlight that long ago had landed on the film in Flaherty’s camera.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. For millions of years, human life was evanescent — a series of infinitely small moments that happened and, just as quickly, vanished. When a person died, their disappearance was complete. Yet, uncannily, Nanook was here on my monitor, grinning at the camera as he watches a record spin on a phonograph and then puts it in his mouth. The pixels I was dragging around in Photoshop were ghosts of things that no longer existed.

I know what became of Nanook (whose real name, deemed by Flaherty to be unpronounceable by the moviegoing public, was Allakariallak). He died, most likely of tuberculosis, two years after the film was released. But since much of my retouching work involved the phonograph record, I found myself wondering about it. It’s not just an abstraction, a symbol of a record. It’s an actual, particular, physical object — something that existed, that had a past and a future.

Someone — we don’t know who, since the label is illegible — had once gone into a studio and sung into a large horn that conducted the sound waves to a needle, which carved a spiral groove into a waxlike coating on a metal disc. A metal “master record” made from that original was pressed into a shellac mixture and trimmed, creating a copy that someone — perhaps Flaherty himself — found and bought in a record store. That record, taken to the Arctic, appeared briefly in front of a camera, leading to its improbable immortality. And then what? It’s unlikely that the record still exists, a century later. It was no doubt listened to many times off-camera, providing entertainment to any number of people. Eventually its groove wore out, or it shattered, or landed in storage in somebody’s basement and was eventually disposed of. Its atoms, no doubt, have long been scattered through the universe. And yet, there it is, reflecting light, holding an unknown human voice, spinning on my computer screen.

When I drive on the lower deck of the Bay Bridge, I look at the countless rivets holding it together, and realize that each of those rivets was put there by a person with a rivet gun. For each, I wonder, who was the person in the early 1930s who hammered in that particular rivet? What did he have for breakfast that day? Did he have a family to go home to? Did he like his work, or would he rather have been an engineer, or a sailor? How long did he live, and how did he die? How can I express my gratitude to him for helping to build the structure that is supporting me right how, keeping me from falling into the bay? Every manufactured object we see embodies a human life (or many lives). The “Nanook of the North” phonograph record, which began with a voice in a studio and found its way into the mouth of an Inuit hunter, exists now only as an illusion, a collection of illuminated dots, but it still carries the spirits of the people who created it and interacted with it. How much more so for the things around us that we can still reach out and touch!

Recent Comments