Double Acting

My first training as an actor came in high school, from a teacher named William A. Lawrence. Though he was nominally an English teacher, his first love was the theater: He directed the school’s drama club, and he often staged one-act plays in his classes.

Bill (as he insisted I call him after I’d graduated) had great fondness for the traditions and lore of the theater; he was the kind of guy who would refer to Shakespeare’s “Scottish play” because it was considered bad luck to utter the name “Macbeth.” But he had no patience for people who put on airs. He had once served in the Merchant Marine, and he wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty. He drove a sturdy old pickup truck, which he often used to haul props, scenery, and even actors.

For Bill, theater was an honorable profession, and acting was an honest day’s work. An actor’s job was to memorize the lines, hit the marks onstage, learn as much as possible about the character he or she was playing, and above all, do justice to what the playwright had written. He often made fun of directors who went on and on about a play’s subtext and a character’s motivations, when all an actor wanted to know was, “Should I say the line louder or softer?” When in doubt, Bill would simply say, “Do it like this,” and he would read the line in such a way that the character came immediately alive.

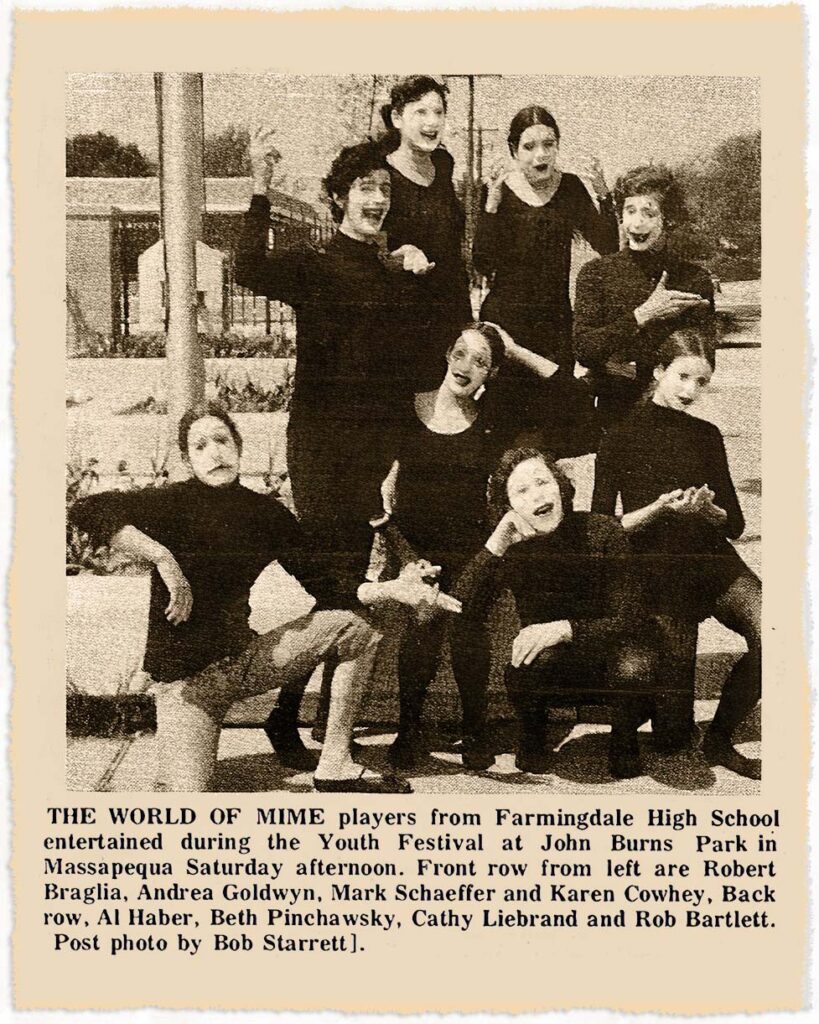

In the late 1960s, Bill had founded The World of Mime, which — so far as I know — was the only mime troupe in the country consisting entirely of high school students. As a child, I had seen occasional mimes perform on television, and I’d also seen comics such as Red Skelton and Jackie Gleason do hilarious skits without saying a word. I grew up imitating them, and it became second nature to me to pull an invisible rope or do a pratfall. So when I got to high school, I naturally became part of the troupe.

We’d tour after school or on weekends, performing at schools, fairs, and community centers around New York. We’d sometimes travel to performances in full white makeup, riding in the bed of Bill’s pickup truck and giving quite a scare to drivers along the way. We never knew what the venue would look like until we got there, and we often had to improvise to adapt to unusual locations (such as a courtroom that had a fixed bar in the middle of the “stage”). After three years of this, I came to consider myself a relatively seasoned performer.

My other influence as an actor was a unique institution called The Fiedel School, on the north shore of Long Island. During the year, Fiedel was a country day school, but during the summer, it ran a creative arts program for kids of all ages — sort of an artistic day camp. I was fortunate enough to attend Fiedel for a few summers, first as a student and later as an apprentice in the drama department.

Fiedel was an anything-goes kind of place, combining a fanatical devotion to creativity with the touchy-feely ethos of the 1970s. Though students ostensibly signed up to study something specific, such as drama, music, or creative writing, the lines between these departments ranged from thin to nonexistent. Fiedel was a place where actors could dance, dancers could sing, and musicians could make jewelry in the silversmith’s shop. Getting formal instruction was desirable, but not essential — any of us had the opportunity to pick up a stray banjo or an upright bass and figure out how to make music with it. The Fiedel approach to acting was completely opposite to that of Bill Lawrence: It wasn’t about study and discipline, but rather about inner experience and improvisation.

I was never a great actor, but I was competent, and by the time I graduated from college, I even managed to find ways to get paid for it. I worked as an actor and mime (among many other things) throughout my 20s — the last few years as part of a touring children’s theater troupe. But when I married Debra and moved to the west coast, my acting career ended. I had no theater connections in the Bay Area, and was too busy trying to establish myself as a freelance writer and producer to pursue any.

Still, the lessons I learned from Bill Lawrence and the Fiedel School have supported me in everything I’ve done since. At Fiedel, I absorbed the attitude that anyone can learn to do anything, that no special training is needed — a mindset that I’ve brought to my teaching and to my own work life. And from Bill, I got the principle that the important thing in any endeavor is to do the work, get it right, and not be pretentious about it. (I imagine that he would have had the same qualms that I have about applying the word “art” to one’s own output.) When I began to lead mime workshops in the 1970s, I synthesized their two opposite approaches to acting, combining exercises to bring out submerged feelings with a vocabulary of technique in which to express those feelings.

Alas, the Fiedel School shut down in 1984, and its visionary founders, Ivan and Roslyn Fiedel, passed on in the late 1990s. William Lawrence — who eventually left teaching to become a professional actor — passed away last year, at the remarkable age of 95. I remain in their debt.