Narrow Escape

At a recent party (during that brief interlude when parties were a thing again), I had a conversation with someone who had attended a wine tasting. He was something of a wine connoisseur, and he spoke derisively of the tasters who had liked the cheaper wines more than the good, complex, expensive stuff. His attitude — although he didn’t express it in quite these words — was “Why should these ignorant people be allowed to drink wine?”

As much as I dislike snobbery, I have to confess that I sometimes share in it. When a new acquaintance told me that he liked blended scotch better than single malt, I couldn’t help but think less of him. It’s one thing to buy blended scotch because you don’t know enough about single malts to be able to pick one out, but to actually like it better…? It was hard to imagine that we could become friends.

I suppose we all have our snobberies — if not about alcohol, then about music, or literature, or fashion. But it only recently struck me that being a snob requires us to go against our usual way of assessing people.

A common, negative thing that one person might say about another is that they’re “narrow-minded.” To be narrow-minded is to be stuck in one set of beliefs, and to dismiss any beliefs that lie outside that set as simply wrong. The opposite of being narrow-minded is to be open-minded, which is to say willing to entertain a wide range of beliefs. If I’m open-minded, it doesn’t mean that I have to accept your view that UFOs are spaceships piloted by aliens from other planets, but I at least have to be open to being convinced. And I have to respect your right to hold that belief, even if it’s one I disagree with.

Of course, there are certain things about which we’re supposed to be narrow-minded. If you express a belief that one race of people is superior to another, I’m expected not only to reject that belief, but to consider you a lesser person. Failing to be narrow-minded in that case would make me a lesser person. But moral issues like that one are in a separate category, because — for mysterious reasons that I’ve speculated about before — we take the moral rightness or wrongness of something to be a fact, not something that we can simply hold beliefs about.

Outside of moral contexts, however, we’re generally willing to concede that our judgment of a particular set of ideas is just that — a judgment. I might consider “Vertigo” to be a better movie than “Santa Claus Conquers the Martians,” but I’d never claim the superiority of “Vertigo” to be an objective fact. The strongest claim I could make is that my assessment of movies aligns more closely with critical consensus than yours does.

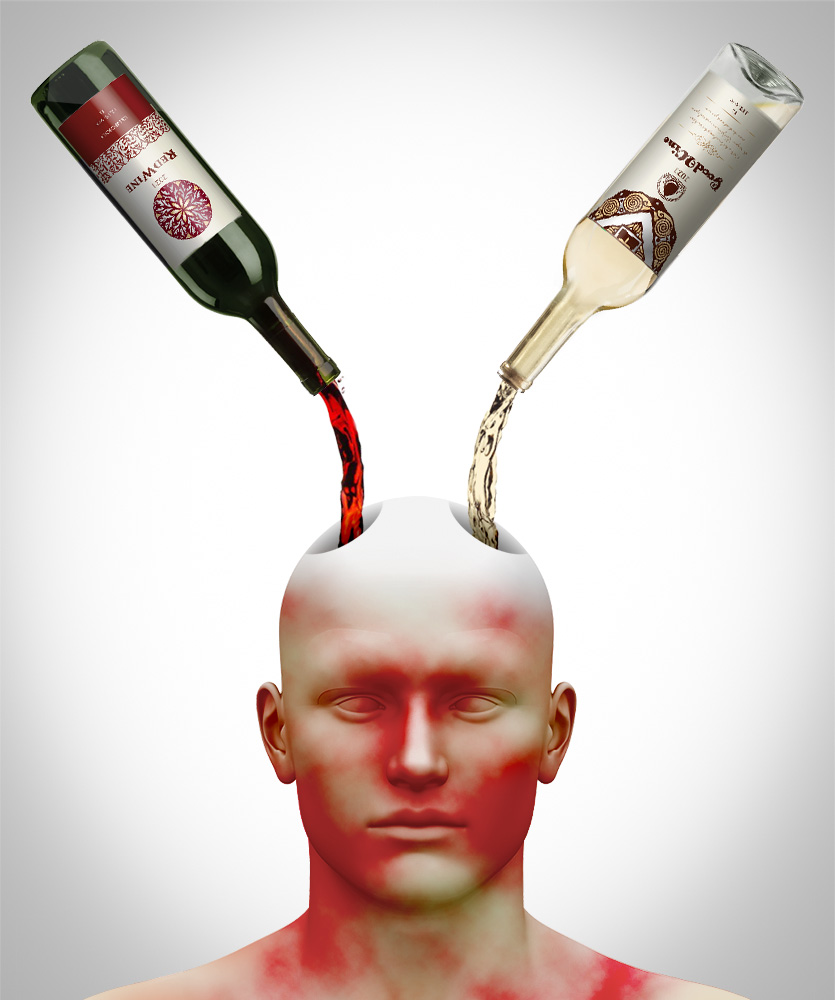

So why is it that we generally admire open-mindedness and scorn narrow-mindedness, but in cases of taste, we experience the opposite? Why am I more likely to respect someone who says “I enjoy rosé wine, but I refuse to drink white Zinfandel” than someone who says “All wine is good”?

After all, a drinker who believes that all wine is good will likely have a happier life, since they’ll take pleasure in whatever is served to them at a party. They’ll be more open to trying varieties of wine that they’ve never heard of before. They’ll have equal regard for each new person they meet, regardless of that person’s taste in wine. What reason could I have to look down on someone like that?

My guess is that snobbery is not really about the wine — or whiskey, or art, or whatever — but about social identity. If I believe in the superiority of a particular style of music, I get to be a member of a tribe, and to bond with people who feel the same way about music. I get treated as an insider, and I get to treat others as outsiders. Deep down, I know that my ranking of one sort of music above another is simply a matter of taste, and not a provable fact; but I get social rewards for treating it as if it were a fact.

I’m coming to feel that it’s incumbent on me to start ignoring those social rewards as a way toward being a better person. When I meet someone who prefers blended scotch, shouldn’t I make a conscious choice not to look down on them, but to chastise myself for my own narrow-mindedness? Shouldn’t I say to myself, “Well, sure, blended scotch is up to 80% neutral grain whiskey, with various proportions of barrel-aged malts added to give it flavor, and it’s mass-produced this way not for reasons of quality, but simply to keep the price down — but if my new acquaintance thinks it’s superior, maybe they’re seeing something that I’m missing”?

OK, well, I didn’t say it was easy.

I want to state as objective fact that the San Francisco Ballet’s version of the Nutcracker is the best in the world.

My issue with someone who would say, “All versions of the Nutcracker are good” is that they’re not reflective. If they’re going to give examples of why they say that, then I wouldn’t have that concern.

There’s so much polarization around all sorts of issues that I question whether open mindedness is prized in the United States.