Professionalism

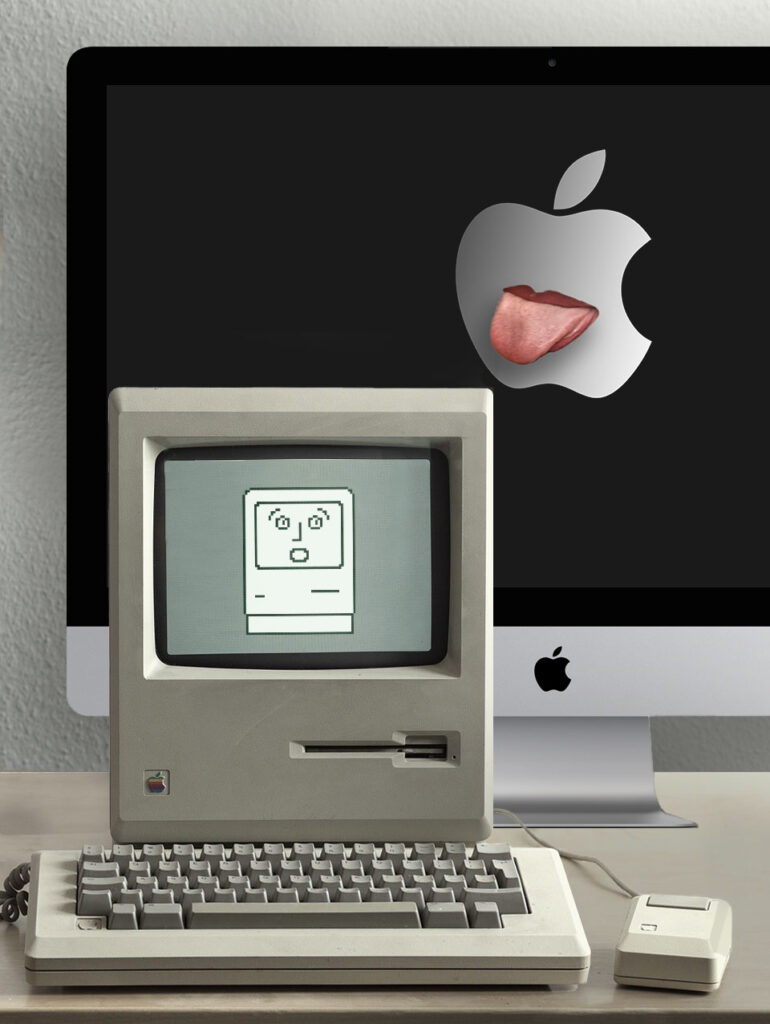

Sometime in 1985, I got a call from a friend. “I just got one of those new Macintosh computers,” he said.

“I played with one for a couple of hours,” I said. “They’re fun.”

“Well, I was thinking,” he said. “You know how they come with those different typefaces? I thought I might offer typesetting services to people, and make some extra money that way. You have a background in publishing — do you think that would work?”

I chuckled, trying not to sound patronizing. “I’m sorry,” I said, “but nobody’s going to accept Macintosh output as camera-ready repro. Those bitmapped typefaces are clunky and amateurish, and the resolution is way too low. Besides, there’s a lot more to typesetting than just typing words on a line. There are subtleties of leading, tracking, and kerning that no computer can handle by itself. You need years of experience to be a good typesetter.”

“Oh, well,” he said unhappily. “The type looks fine to me, but I guess you know what you’re talking about.”

In my defense, I should note that in 1985, the Macintosh was still basically a toy. The introduction of laser printers and PostScript fonts was still a year away. Typefaces on the Mac were designed to be printed out on the Imagewriter, a dot-matrix printer. They looked better than previous dot-matrix output, but definitely could never be mistaken for the clean, elegant type that we were accustomed to seeing in books and magazines.

I was astonished, therefore, to begin seeing printed publications using Mac-generated type arriving in the mail, no more than a month or two after I told my friend what a silly idea that was. I had clearly been wrong in thinking that the years of experience and the critical eye that professional compositors brought to their craft was something that people valued.

Cut to ten years later, when my wife and I had a successful business producing educational and training videos for business and nonprofits. I’d sent a proposal and a demo reel to a prospective client who’d seemed pretty interested in hiring us. The client responded by sending us a sample video he’d received from another producer. “I still like your work,” he said, “but this guy is offering to do the job for less than half of what you’re charging. How is that possible?”

“Your guy isn’t using professional equipment,” I said after viewing the video. “He shot this with a consumer camcorder with a built-in camera mic. The image isn’t as sharp and clear as it ought to be, and the audio isn’t clean. He shot it in natural room light instead of using studio-quality lighting. He seems to have done it himself instead of using a crew. If you’re satisfied with that level of quality, then go with him. I certainly can’t match his price.”

Once again, I assumed that the marks of professionalism were important, and once again, I was wrong. The client accepted the other producer’s bid. And at that point, I began to wonder whether my priorities were wrong. The fuzzy, Mac-generated type had communicated the same information that traditionally set type would have. And the video shot with the consumer camcorder was every bit as educational as what I was shooting with my professional crew and equipment.

I started finding ways to integrate desktop technology into my production workflow, and the lapse in professional polish was apparently not noticed by my clients. Today, of course, the tremendously increased power of desktop computers and software, along with parallel advances in cameras and lighting, make the quality of digital video so remarkably high that it’s hard to remember a time when anyone had to be concerned about a trade-off. But I’ve continued to wonder what other indicators of professionalism are ready to fall by the wayside. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, TV, radio, and podcasts have generally been homemade, often with consumer-grade equipment, and audiences don’t seem to mind. Professionals of every stripe are allowing themselves to be seen onscreen in casual dress, with gray roots and grown-out hair, and the quality of their work clearly hasn’t suffered. Maybe it’s again time to put our emphasis on the inherent value of what people do, and to forget the attention to appearances.