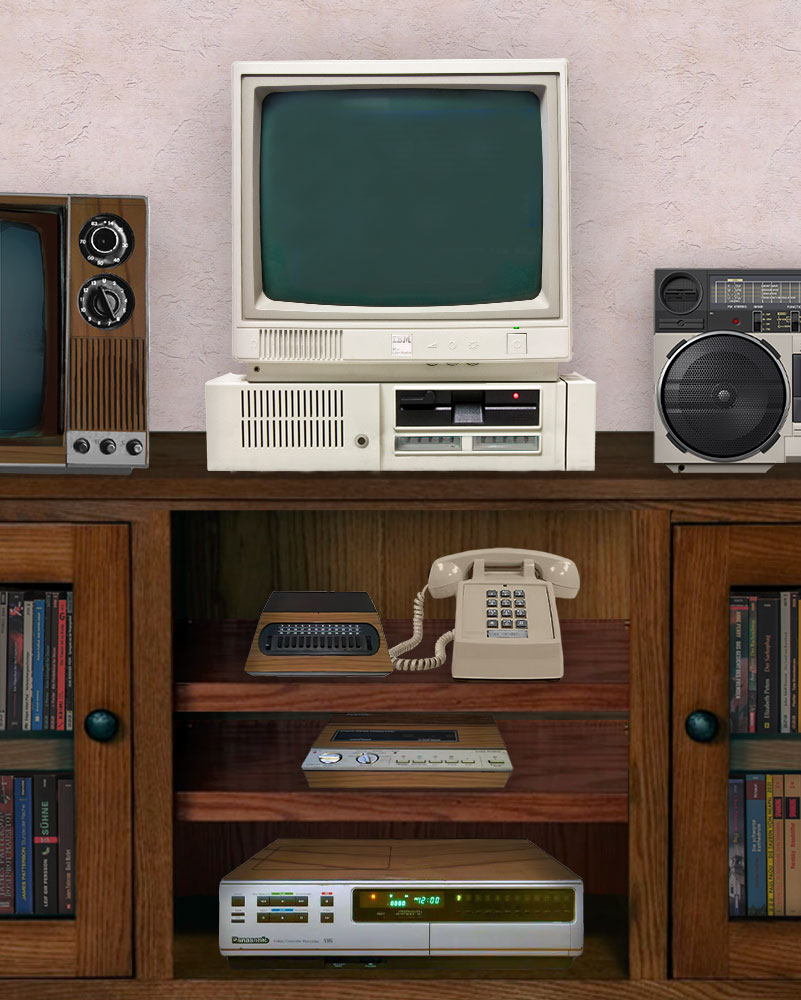

I know that you’re not interested in hearing about my first computer — an IBM PCjr with a single floppy drive, a 4.77 kHz processor, and 128 kb (yes, that’s kilobytes) of memory. When an old guy like me talks about how rough he had it compared to kids today, you naturally want to tune him out and go back to your phone.

The thing is, though, I didn’t have it rough. I loved my PCjr. How was I to know that it would be totally obsolete in a couple of years? At the time I bought it, it changed my life. I no longer had to remember and process loads of information in my head — I could outsource it to a machine. I could write, edit, and type a finished draft, all at the same time. With the addition of a modem, I was able to communicate with people anywhere in the world, do research, and even buy things without having to leave my studio apartment.

Those of us who grew up before the 1980s tend not to think much about that decade. The 1970s had disco, energy crises, and hard-fought rights for women and gay people; the 1990s had hip-hop, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the World Wide Web. But what did the 1980s have, other than mixtapes and Ronald Reagan? Personally, I passed some important milestones during that decade: I quit my secure publishing job to go freelance; I met and married my wife; I moved with her from the east coast to the west. Putting aside those personal events, however, I think of the 1980s as the time when the technological environment that we now take for granted began to take shape.

In addition to the aforementioned computer, the 1980s brought my first phone-answering machine, my first cable TV, my first VCR, and my first microwave oven.1 For the first time, I was able to get money out of a machine anywhere in the world, instead of having to go to my local grocery store to cash a check. Cash itself was less necessary, as bank-affiliated credit cards had become ubiquitous. Thanks to the same network infrastructure that made ATMs possible, sellers were now able to approve credit card purchases instantly, without having to manually look up deadbeat card numbers in a printed booklet.

Deregulation of the aviation industry made flying affordable to people who were not well-to-do. In some cases, it was more than affordable — an upstart airline named People Express offered flights from New York to Boston or Washington, DC for $29 (sometimes discounted to $19), making it easy to visit distant friends. Flying People Express was an adventure. There were no tickets; passengers would stampede onto the plane until all the seats were taken, at which point the doors would close. Not until the plane was in flight would a flight attendant wheel a cart down the center aisle, taking each passenger’s credit card and printing it through several layers of carbon paper with a satisfying ka-chunk.

I would venture to say that before the 1980s, the average person’s lifestyle would have been comfortably recognizable to someone from the 1950s. By the end of the 1980s, it was entirely different. I remember the day when I suddenly grasped the possibilities of this new era. I was in a city — I don’t recall which one, because my frequent People Express flights have all blurred together — with a friend, and we decided to split up and meet later. But in those days before cell phones, how could either of us let the other know if we’d been delayed, or if we couldn’t find each other?

“I know!” I said. “We can use my phone-answering machine.” It had recently become easy and cheap to make long-distance calls from a pay phone, thanks to the emergence of new networks such as MCI and Sprint. If either of us had an urgent need to contact the other, we could call my machine back in New Jersey and record a message. And if either of us was concerned about the other’s whereabouts, we could call my machine to check whether a message had been left. This was not what answering machines were invented for, but their existence had nevertheless opened the door to something formerly impossible: two people making contact when they couldn’t find each other in a big city. What other previously unimaginable things would we soon be able to do?

Coda: Most of those life-changing innovations from the 1980s are either gone or going away. Nobody uses answering machines anymore. VCRs are a thing of the past, and cable TV is rapidly being eclipsed by streaming services. ATMs are far less necessary, due to the growing reliance on cashless transactions and the ability to deposit checks remotely. Long-distance phone networks such as AT&T, MCI, and Sprint have been supplanted by wireless carriers (although some of those familiar names remain). Even desktop computers — the descendants of my primitive PCjr — are fading in popularity, with many of their functions being taken over by smartphones, tablets, and wearables. Still, many aspects of the way we live now can be traced back to the big technological shift that began forty years ago.

Interestingly, the one thing that still exists virtually unchanged from its 1980s precursor is the microwave oven. It’s hard to remember what life was like before it became a standard kitchen appliance. Come to think of it, it’s not that hard, since my house’s microwave oven recently broke down, and we were at a loss as to how to reheat leftovers. I poured my day-old Chinese food into a pot and impatiently stirred it over a gas flame. The others in the household ate theirs cold.

Recent Comments