When my mother was told, eight years ago, that nothing more could be done to treat her pancreatic cancer, she was undaunted. She was not about to let something as important as her death escape her control. She somehow managed to enter hospice over Labor Day weekend, making it as convenient as possible for all of the out-of-town relatives to fly to her Florida hospital room. She told us exactly who should cater her shiva, and instructed us to order food for 75 people. (Taking into account my mother’s popularity, we instead ordered food for 100 people, and ended up with precisely 25 people’s worth of food left over.)

Most important, she had long since arranged and paid for her funeral and burial. (She was proud of having nabbed “waterfront property” for her gravesite, which was her half-serious way to describe its location next to one of the cemetery’s small ponds.) All we, her offspring, had to do was go to the funeral home and sign some papers.

There was one small omission in her planning. “Did she belong to a synagogue?” the funeral director asked us. The answer was no — her second husband, Eddy, had never been a fan of attending services. “Well, we’ll need to get a rabbi to officiate at the funeral,” the director said. “What kind of rabbi do you want?”

I was not prepared for that question. It hadn’t occurred to me that rabbis came in kinds. For lack of a more sophisticated response, I said, “A rabbi with a sense of humor?” That turned out to be the perfect answer. “Ah, I have just the right person for you,” the funeral director said, and the rabbi we were matched with did turn out to be an ideal choice.

What strikes me now is how the funeral director phrased the question. She did not ask — as she well might have — “What kind of rabbi would your mother have wanted?” Clearly, the rabbi’s primary function was to make us, the mourners, feel comforted. My mother’s preferences, whatever they might have been, did not need to be taken into account. She was, after all, dead.

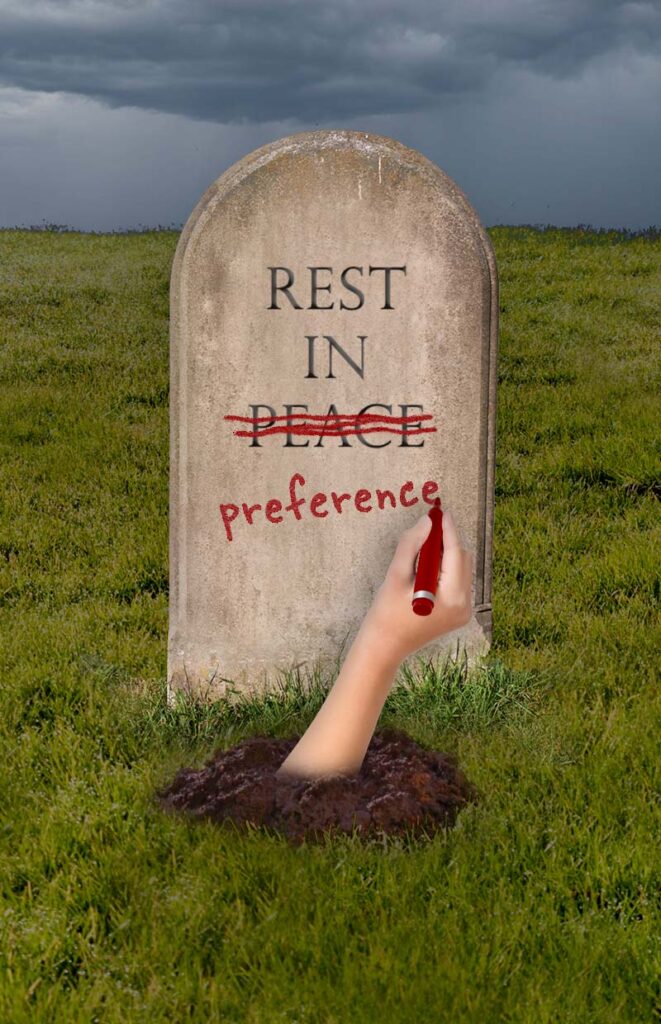

The reason I need to state this so bluntly is that people’s condition of being deceased rarely seems to get in the way of their wishes being carried out. I’m puzzled by the deference that’s given to the feelings of someone who is no longer equipped to have any.

I’m happy that my mother planned her funeral in advance — not because that allowed her to have the funeral she wanted, but because doing so took the burden of arranging it off her survivors. I’m grateful that she made a will — not because it means that her property was distributed in a way she would approve of, but because it relieved her survivors of having to squabble over who was entitled to what. For some reason, actions that I consider altruistic — done as a favor to the next generation — are routinely treated as if their sole purpose is to benefit the deceased. This makes no sense to me, because short of resurrection, nothing can be done to benefit the deceased.

These thoughts come to mind because of an article that I recently read in The Guardian, about the man who pretty much invented the idea of dead celebrities’ likenesses being owned by their estates. It had previously been established that celebrities were legally entitled to “publicity rights” — the right to decide who got to make use of their names and faces, and for what purposes. This made perfect sense, since living celebrities might object to being portrayed as endorsing a cause, or a product, that they didn’t in fact support. Secondarily, it gave those celebrities the sole right to profit — or to license others to profit — from their hard-won fame.

In the early 1980s, a lawyer named Roger Richman promoted the idea that since publicity rights constituted a financial asset, they could be inherited after a celebrity’s death, just like any other asset. He became well known for his aggressive representation of the estate of Albert Einstein, immediately suing anyone who put Einstein’s face on a T-shirt or otherwise used his image for a purpose not authorized by Einstein’s estate. His litigiousness is estimated to have earned $250 million for the Hebrew University, which currently owns Einstein’s publicity rights.

But publicly, this financial arrangement is portrayed as being for Einstein’s benefit — protecting his image from being sullied by association with ideas or organizations that he would not have approved of in life. For example, Einstein’s persona may not be used to promote tobacco, alcohol, or gambling (which is interesting, since he is well known for his habitual pipe-smoking).

It’s quite possible that Einstein’s heirs do feel a moral duty to maintain the purity of his reputation, apart from whatever financial gain that continued purity brings them. They’re certainly entitled to hold that belief, if it brings them comfort. But we need to dispense with the fiction that this protection is somehow owed to Einstein himself, because it’s “what he would have wanted.” Einstein died 67 years ago, and any wants he might have had died along with him. There are a number of things that dead people cannot do, and holding opinions is one of them.

Recent Comments