I must have been very young when my mother first referred to me as right-handed. I asked her what this meant, and she explained that a right-handed person accomplished most tasks with their right hand. I took this to be an important piece of information.

“Then what’s my left hand for?” I asked. Her answer — and I remember this distinctly — was, “Your left hand helps.”

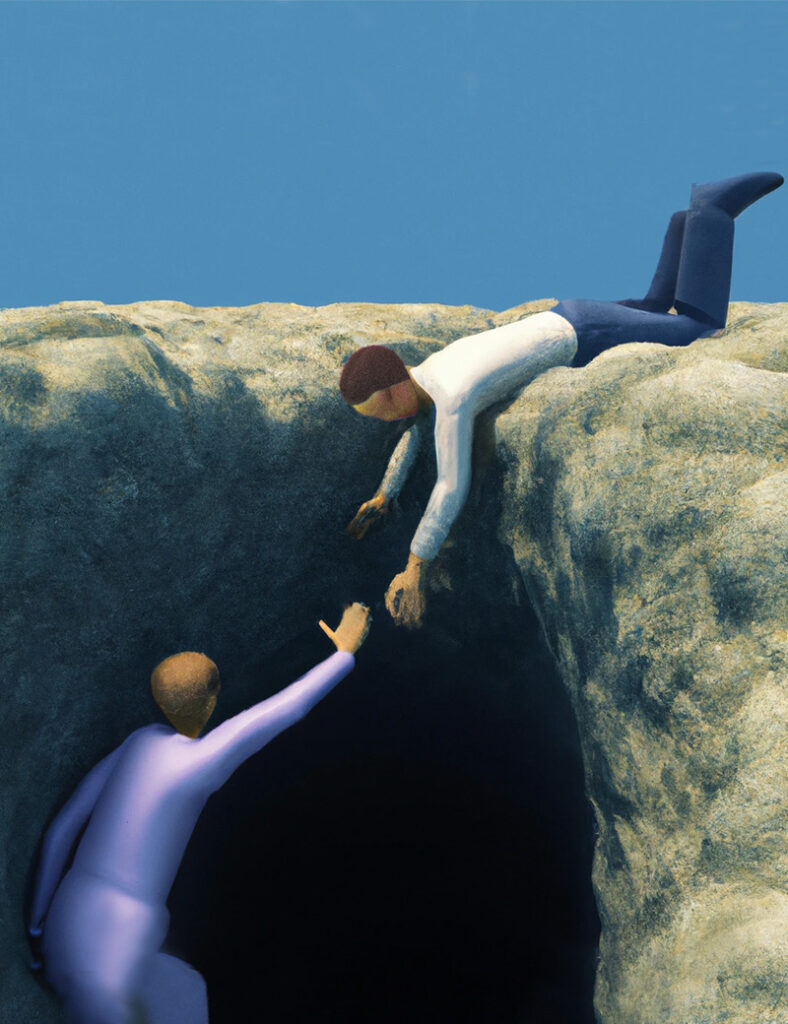

That seems like an innocuous enough reply, but at the time it sent me into a days-long spiral of worry. I imagined myself encountering someone who had fallen in a hole, and extending my arm to pull them out. Under such urgent circumstances, would I remember that this was an instance of “helping,” and therefore know to do it with my left hand? What would happen if I didn’t? Would the person refuse my outstretched right hand? If they did take it, would I be unable to help them? Would I be able to switch hands at that point, or would it be too late? What if, heaven forbid, the person were heavy and I needed to use both hands?

Looking back, I can see that this was a simple category error: I misapprehended the concept of handedness, which is intended to be descriptive, by interpreting it as prescriptive. But I’ve come to realize that it’s an error that’s often repeated, and not just by me.

When I entered junior high school, the need to travel to a new classroom for each subject (unlike in elementary school, where we would spend the whole day in one room) necessitated carrying books through the hallways. Very early on, I was informed by my peers that I was holding my books wrong. I was cradling them against my chest with one arm, the way the Statue of Liberty holds her stone tablet. It was made clear to me, with abundant snickering, that this was the way girls carry their books. As I boy, I was supposed to carry them against my hip, with my arm down at my side.

“How do you look at your fingernails?” I was asked. I held out my hand, palm down, with my fingers splayed. That, too, was wrong. As a boy, I was supposed to look at them with my palm up and my fingers curled over. There were probably some other tests too — I can’t recall — but if there were, I almost certainly failed them.

Motivated by the threat of relentless teasing, I soon learned to adopt acceptable masculine habits. But this, clearly, was another instance of descriptive rules being applied prescriptively.

I’m reminded of the all-too-common situation in which my cat, Mary Beth, steals food off the kitchen counter. “That’s not cat food!” I’ll tell her. Her obvious reply (which I believe I first saw in a New Yorker cartoon) would be, “I’m a cat. I’m eating it. How is it not cat food?”

In the same way, I logically should have been able to say, “I’m a boy. I’m carrying books. How is this not the way a boy carries books?” But unlike using the left hand for helping, rules like this are — for no good reason — actively enforced through societal pressure.

Children are not the only ones who apply descriptive rules prescriptively, of course. When, as a kid, I expressed a liking for bologna sandwiches in white bread, my mother protested, “Jews don’t eat bologna, and they don’t eat white bread!” When, in my senior year in high school, I elected to take a typing class, she objected, “Smart kids don’t study typing!”

Whether these battles are won or lost really doesn’t matter. (As it turned out, I did get to eat bologna-on-white bread sandwiches for lunch, and typing turned out to be the only useful thing I studied in high school.) I suppose that if I really wanted to resist the pressure to carry my books in a certain way, I could have; in that case, it just wasn’t worth it to me.

But it would be nice if, every time we’re tempted to make a prescription out of something that’s merely descriptive (and of course I’m as guilty as anyone! How many times did I say to my students, “That’s not the way a professional would do it”?), we could stop for a moment and say, “Why not?”

Recent Comments