(part three of three)

Most of what I need to know in life was taught to me in elementary school. I learned the general outlines of American and world history; I learned the basic facts and principles of biology and physics; I learned enough math to make whatever calculations were likely to be required in my day-to-day life. I learned how to think critically, write clearly, and use the resources of a library. All in all, what I’d learned by the time I reached adolescence seemed perfectly adequate to prepare me for adulthood. The only useful knowledge that high school added was learning how to type and how to drive.

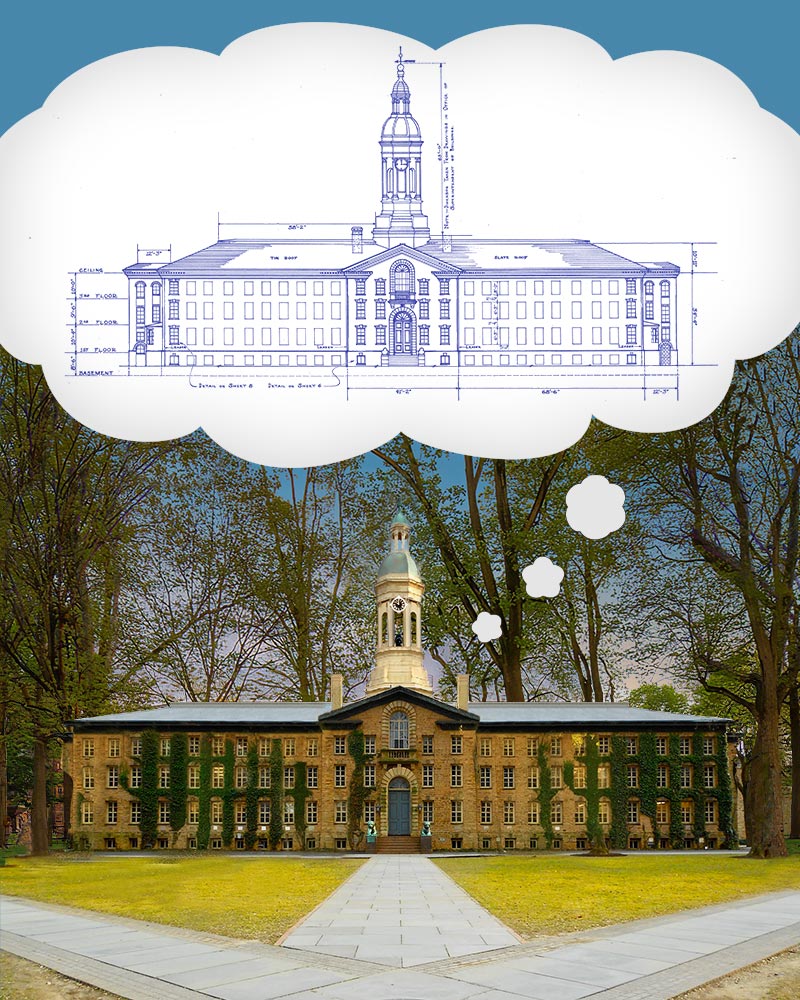

When I started out at Princeton, it was with the assumption that I’d develop an affinity for something, and I trusted that at some point I would know what that “something” was. In the meantime, I nibbled from a buffet of introductory courses, hoping to be exposed to a maximum of new perspectives with a minimum of frustration.

Over the years, I saw the students around me get swept up by one intellectual passion or another. When I took Architecture 101, I found the course to be trivial and pointless. My friend Sarah, who took the very same course from the same professor, found it so inspiring that she decided to pursue architecture as her life’s work. My roommate Krishna, who took introductory Latin and ignominiously failed the course, fought to be allowed to take the same course again, because he really wanted to learn Latin. A biology major named Jenny planned to spend the summer doing field work in Peru, not because she was required to, but because she was particularly interested in learning about a particular species.

I waited in vain for my own inspiration to appear. Though I enviously watched the bolt of lightning strike everyone around me, it always managed to pass me by. It’s not that I lacked passion, but the real questions that concerned me were those that scholarship seemed ill equipped to pursue: Why do I exist on this planet, and what is the meaning and purpose of my life?

All Princeton had to offer in response to such questions was to tell me what people thought. Johann Sebastian Bach thought that the role of music was to glorify God. Thomas Jefferson thought that architecture ought to uplift the citizenry and inspire civic virtue. Bertolt Brecht thought that drama ought to keep audiences at an emotional distance so they could make rational judgments about the morality of the characters’ actions. The library was filled with famous people’s thoughts. But were they right? If they weren’t, who cares what these people thought?

I ended up majoring in philosophy, not because I seriously held out hope of finding definitive answers to life’s mysteries, but because philosophy at least addressed those questions straightforwardly. Unlike writers and artists, philosophers were not permitted to make things up, or to spout mere ideas and impressions; they had to justify their assertions by means of logical argument. Plus — in a tradition that began as far back as Socrates — prior learning, and the assumptions that came with it, were considered by philosophers to be a liability rather than an asset. When people asked my why I’d chosen to study philosophy, I said — sincerely — that it was because philosophy is the only field where I wouldn’t have to claim to know anything.

It quickly became clear, as I’d suspected, that there was no universal truth to be found in the philosophy department. Basically, what philosophers do (and therefore, what philosophy students do) is write papers. A philosophy paper — or journal article, or book — consists of the following elements, though not always in the same order:

- Summarize an argument that another philosopher has made

- Point out flaws in the argument

- Propose a variation on that argument, or a different argument altogether, that eliminates those flaws

- Point out possible objections to the newly proposed argument

- Explain why those objections are wrong

Since no philosophical argument is ever perfect, this cycle can go on continuously — and it has. So far as I know, in more than two thousand years of Western philosophy, no undisputed fact has ever been established. Philosophers are still debating arguments made by Plato in ancient Greece.

I got through Princeton, as I’d gotten through all my previous years of school, by my ability to write convincingly. Writing philosophy papers — not to mention a senior thesis — probably even improved my writing, since it trained me to be precise when I might otherwise be tempted to fudge. (Later in life, when I tried my hand at writing marketing materials, clients criticized my work for being “too clear.”) But I can’t truthfully say that studying philosophy taught me anything useful about the world.

I still value my college experience, and I’m sure my Princeton degree has opened doors for me. But I can’t say confidently that I earned that degree, or that my spot at the school might not have been made better use of by someone else. I still don’t have any answers to life’s big questions, and I’m still not convinced that institutions of higher learning are the place to find them. Perhaps the world is meant to be experienced rather than analyzed. Speaking for myself, I still get as much pleasure from a glass of good whiskey as I do from a good book.

Recent Comments