A while back, I began a blog post called “Sound Barrier” with this sentence:

The first Broadway show I ever saw was “Hello, Dolly!,” which had recently been recast with Pearl Bailey and Cab Calloway in the lead roles.

My wife Debra, who vets everything I write before I post it (partly to catch typographical errors, but mostly to make sure I don’t say anything inappropriate) flagged that sentence. “You can’t follow an exclamation mark with a comma,” she said.

“But the exclamation mark is part of the title of the show,” I said. “It’s not punctuating the sentence.”

“It’s still not right,” she said.

I came away grumbling. I had to admit that it did look funny, but I didn’t want to have to rewrite the sentence. A few days later, I happened to pick up the November 30 issue of The New Yorker, and found the following sentence in an article about William Faulkner:

In these books, no Southerner is spared the torturous influence of the war, whether he flees the region, as Quentin Compson does, in “The Sound and the Fury,” or whether, like Rosa Coldfield, in “Absalom, Absalom!,” she stays.

“The New Yorker did it!” I said. “They put a comma after ‘Absalom, Absalom!’ ” That definitively settled the argument. To borrow a formula from Richard Nixon, if the New Yorker does it, it’s not illegal.

The fact that Debra and I can quibble about the finer points of grammar and punctuation — but not about much else — is one of the delights of our relationship. Mostly, our complaints are not with each other, but about errors we find in other publications: things like the use of “literally” to mean “figuratively,” or the misuse of an apostrophe to form a plural.

Lately, though, we’ve been feeling like members of a rapidly shrinking minority. When she gripes about someone who used “unique” to mean something other than “the only one of its kind,” I have to tell her, “That battle’s been lost.” Meanwhile, I go on fighting for even more hopeless causes. When I complain about the use of “as such” to mean “therefore,” or insist on use of the subjunctive mood to describe a hypothetical event, my Facebook friends invariably tell me that it’s time to give up.

These issues are of more than theoretical importance, because I don’t know how critical I should be of my students’ writing when I teach college courses. I’m not an English teacher, so enforcing the rules of written language is not strictly my job. At the same time, I caution my students that no matter how good they are at what they do, no one will take them seriously if they can’t communicate well about what they do. If they want the respect of their employers, clients, and peers, they need to use proper grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

However, I’m not sure that this is true anymore. When I look at the memos that come from several college administrators, or the classroom materials that are written by some of my fellow instructors, the quality of their writing is not much better than that of my students. Nevertheless, those people have managed to rise to positions of authority. Maybe we’re at the point where not many people pay attention to the old rules. If the people who will be hiring my students don’t know much about spelling or grammar, why should my students have to?

I’m also not convinced that students can internalize the rules of grammar and punctuation if they haven’t grown up reading books that follow those rules. My childhood was kind of unusual in that much of the reading material in our house had been picked up at rummage sales. We had an encyclopedia that had been published in 1912, and a series of fairy tale collections (“The Red Fairy Book,” “The Blue Fairy Book,” and so on) that Andrew Lang had compiled in the 1890s. As a result, from the time I learned to write, my writing had sort of a Victorian style — formal and somewhat distant, with lots of polysyllabic words and compound sentences. (Come to think of it, that pretty well describes my writing style even now.) I don’t see how students who grow up reading tweets and websites can develop a sense of what formal language is supposed to sound like.

So maybe it really is time to give up on preserving arbitrary rules, and just focus on clear writing that communicates clear thinking. After all, when we see a sign that says “Vegetable’s for sale,” we still know what it means, despite the unneeded apostrophe. If someone says, “Tell me if you agree,” we understand that they want us to let them know whether we agree, not to notify them only in the event of our agreement. So far as spelling goes, William Shakespeare famously spelled his own name in several different ways, and yet still seemed to do OK for himself.

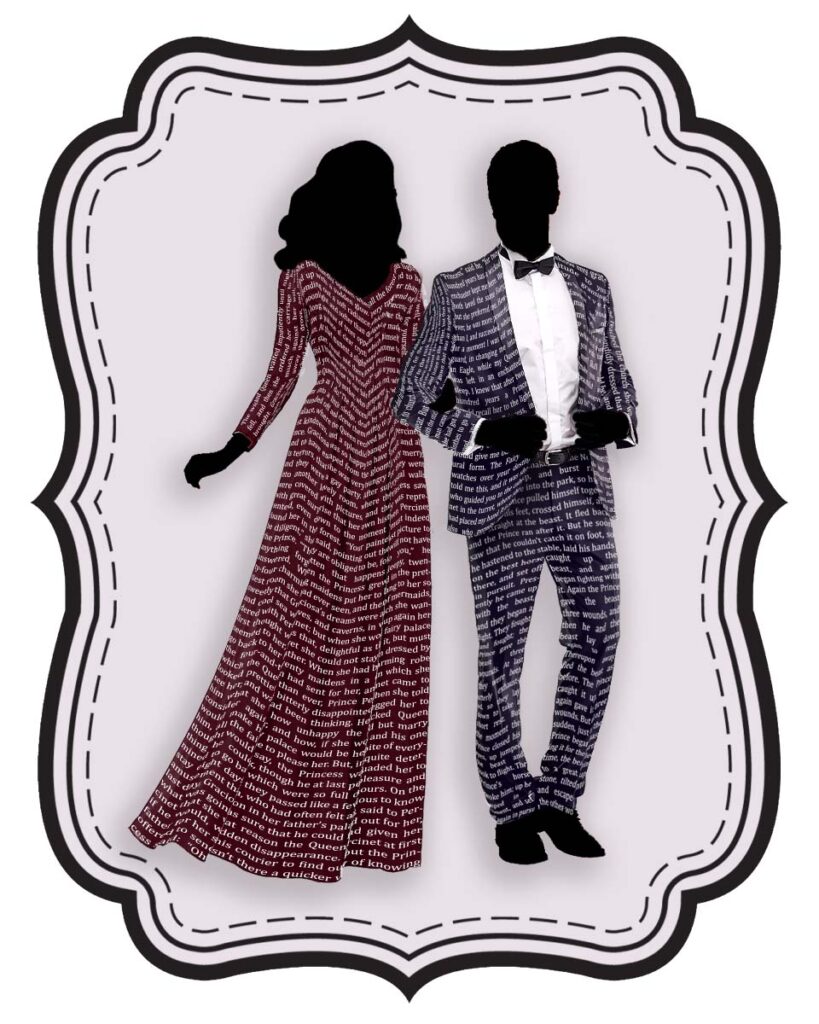

In talking to students, I’ve always compared language to clothing. Just as the practical purpose of clothing is to keep us warm, the practical purpose of language is to communicate. But clothing goes far beyond that basic function. What we choose to wear, and how suitable our wardrobe is to the place where we wear it, is how we tell people what we want them to think of us. Similarly, the style of language that we use, and its suitability to the environment we’re in, necessarily affects people’s assessment of our character.

I think that’s still true. But just as the rules about formal attire have relaxed greatly over the past few generations without any great harm to society, I suspect that the rules of formal language might need to be relaxed as well.

Recent Comments