The community synagogue was the center of my parents’ social life in the 1960s and ’70s, and at least once a month they would attend one of its fundraising events — casino nights, galas, auctions, and rummage sales. Unfamiliar with the word “fund,” I construed that my parents were going to “fun raisers,” and I lamented that I wasn’t old enough to participate in raising the fun.

The event I (vicariously) enjoyed the most was the annual Journal Dinner, a formal-dress affair at which each participant received a copy of the “journal.” The journal was a magazine-sized publication in which members of the congregation could buy ads — a single line, an eighth of a page, a quarter of a page, and so on up the affluence scale, with the most expensive being a full-page ad printed on metallic paper. Each ad consisted of the name of the donor (or, more often, the donating couple) in bold type, optionally accompanied by “Best wishes,” “In honor of…,” or “In memory of….” That was it — the journal had no other content besides the ads, arranged in increasing order of extravagance. I loved leafing through the journal the morning after the dinner and discovering who had bought what. I was perpetually embarrassed that my parents could only afford an eighth-page ad, but I loved getting to the end of the journal where the rich people were gathered, and seeing each donor’s name tastefully emblazoned in the center of a gleaming silver or gold page.

Another synagogue fundraising event that my parents (or, more likely, just my mother) attended annually was the fashion show. Unlike the Journal Dinner — which I understood as a clever means for members of the congregation to flaunt their wealth by buying a bigger ad than their neighbors did — the idea of a fashion show made no sense to me. When I asked my mother to describe a fashion show, she said that it was an event where models dress up in fancy clothing and an audience pays to look at them. That can’t be right, I thought to myself. People pay to watch other people wear clothes? Don’t we do that every day for free?

Eventually I learned that there was such a thing as styles of clothing, that they changed periodically, and that people were always eager to find out what the new styles would be. Wearing the most fashionable clothes was somehow equivalent to buying a full-page ad in the journal. I remember my mother joking about how every few years, the fashion designers would proclaim, “Up with the hemlines!” and women would run out to buy shorter skirts and dresses; then, a few years later, the designers would proclaim, “Down with the hemlines!” and women would run out to buy longer ones. At first I thought that these proclamations were rules that women were somehow required to follow; it wasn’t until later that I realized that women (and men, with regard to the widths of neckties and lapels) were doing so voluntarily.

My response to this newfound understanding was to refuse to wear anything simply because it was in style. What was the point of buying something that was fashionable now, if it’s going to look silly in a couple of years? When bell-bottoms came along in the late 1960s, I insisted on continuing to wear traditional pants. Same with designer jeans in the ’70s. I remember my father treating me to an appointment at a then-novel “men’s salon” (as opposed to a plain old barber shop) in preparation for my sister’s Bat Mitzvah, and watching in shock as the hairdresser, after meticulously cutting and blow-drying my hair, went in with his fingers and deliberately mussed it up. “What are you doing?!” I said. He replied, “That’s the style now. You don’t want to appear too careful.” I would have none of it. If he was going to demand an outrageous amount of money to cut my hair, the least he could do was comb it neatly.

Because my aversion to following the dictates of fashion seems so common-sensical to me, I tend to forget that other people don’t share that attitude. When I was teaching digital-arts classes, students would often ask me to teach them to recreate a particular look or technique that they’d recently seen online. “Why do you want to do that?” I would say. “It’s just a fad.” It didn’t occur to me until later that if these students were going to be graphic designers, they were supposed to latch onto design trends.

Of course, I understand and appreciate that styles evolve over time. If they didn’t, the music world would never have had ragtime, jazz, rock, and rap, and the art world would never have had impressionism, expressionism, and modernism. One thing bothers me, though: In most realms, the emergence of a new style doesn’t necessitate the disappearance of an old one — the old and new can coexist. Symphony orchestras still play the music of Bach and Mozart alongside Thomas Adès and Caroline Shaw. The walls of art galleries still display figurative art along with abstract works. But when a new style of clothing comes along, nobody continues to make the old ones.

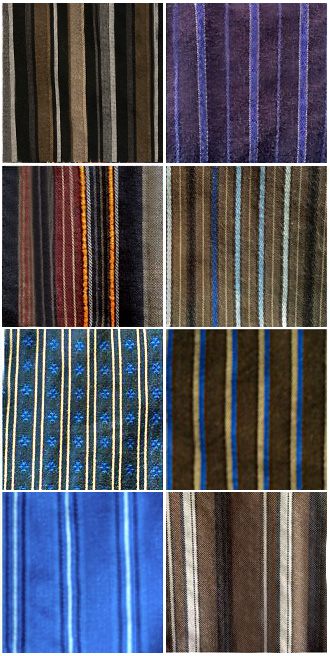

For years, I routinely wore long-sleeved cotton shirts with vertical stripes in dark, saturated colors. (See the photo at the top of this post.) They’re really the only shirts I feel comfortable in, and they used to be ubiquitous — I could easily pick up an armload of nice shirts from the tables at Costco. Then, about ten years ago, they disappeared. Dress shirts now are available only in shades of pink, purple, or blue, and in solids or checks — never stripes. The kind of shirts I like are so out of date that I can’t even find them in thrift shops anymore. To me, they seemed standard and timeless. If I’d known at the time that they were only a temporary fad, I would have hoarded a lifetime supply.

If anyone sees shirts like these presented as a new look in a fashion show, please let me know.

Recent Comments