To a Degree

My brilliant friend Lisa Rothman — entertainer, entrepreneur, and corporate trainer — recently left a comment that got me thinking. (If you find Lisa’s name familiar, it’s probably because she leaves thoughtful comments on pretty much everything I post here.) “I would love to live in a society,” she said, “[that’s] structured around people being able to spend all their time doing the things that they are really good at and enjoy doing.”

I would, too. I’m not entirely sure how that would work, given some serious obstacles:

- The things that people enjoy doing are not necessarily the things that they’re good at, and vice versa.

- There is likely to be much disagreement about what it means to be good at something, and who is and isn’t.

- The things that people enjoy doing don’t necessarily benefit anyone other than themselves, and in some cases might even cause harm.

- It’s not at all certain that the things people are good at, or the things they like to do, are evenly distributed enough to ensure that all necessary tasks get done. (How many people like cleaning toilets?)

Nevertheless, I do think that principle could be applied more often than it is. One place to start might be an area where I have some experience: higher education.

Community colleges, such as the one at which I was a faculty member, have been put under great pressure to model themselves after fast-food corporations. Just as McDonald’s enforces uniformity among its retail outlets, making sure that a hamburger sold at a McDonald’s in Kansas City tastes exactly like a hamburger sold at a McDonald’s in Miami, community colleges are supposed to require uniformity in their curriculum and in the people who teach it. A student who takes English 101 from one instructor is supposed to have exactly the same experience, and (measurably!) learn exactly the same things, as a student who takes the same course from another instructor. The course outline has been rigorously developed and approved by a committee, and it must be adhered to.

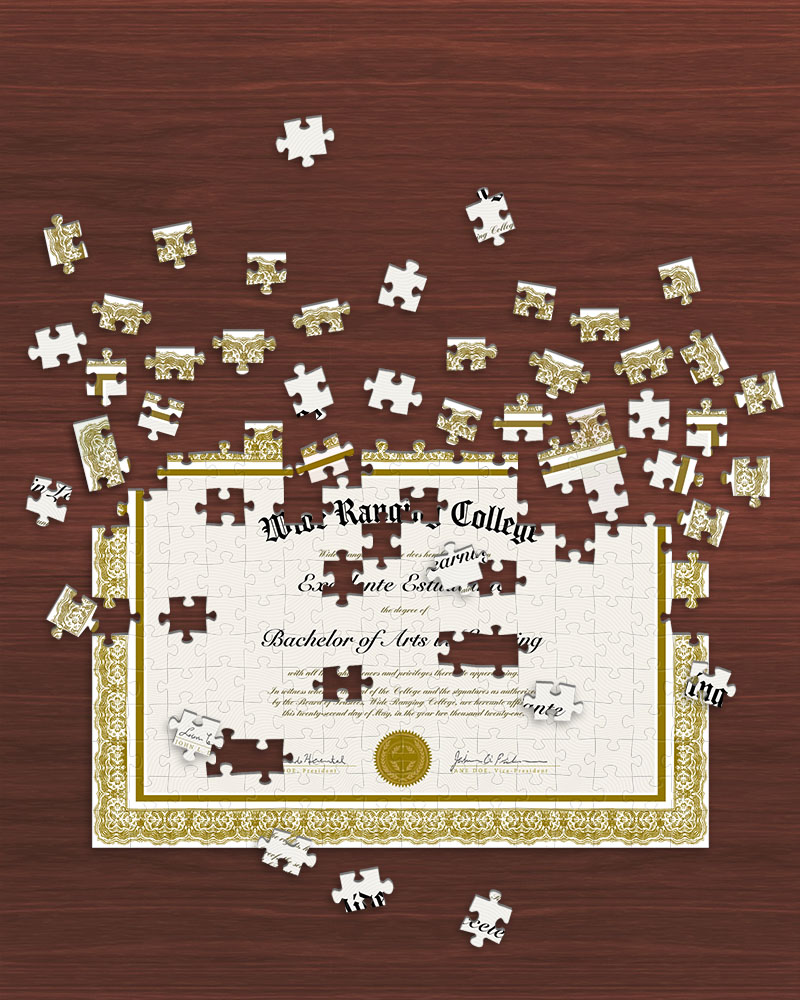

Naturally, there are good reasons for this demand for uniformity. Students who enroll in an advanced course must all be presumed to have received equal preparation in their earlier courses. Transfer students must have taken courses at their first school that are aligned with those as their next school. Students who graduate with the same degree must possess the same knowledge and skills, or else the degree has no meaning.

But it’s clear that something precious is being lost here: the value of each individual teacher’s life experience. In Lisa’s words, every instructor has something different that “they are really good at and enjoy doing.” Wouldn’t the students benefit if the teacher were free to teach that? For example, I’m no expert in desktop printing, because nearly all of my Photoshop work is intended for use online, but I have to teach it anyway because it’s part of the curriculum. I have lots of experience in preparing graphics for video, but I can’t share that experience because it’s not included in the official course outline. Because of my background in theater, I enjoy creating projections for stage productions, but that’s obviously not thought of as a mainstream activity.

What makes this particularly sad is that the specific topics that are being taught don’t matter much. I’ve always told my students, “Everything you do here is going to be obsolete in ten years.” What they really need to learn is how to learn — how to be curious, how to think critically, how to take responsibility for and pride in their work, how to start with fundamental principles and apply them to new situations. The actual subject matter of the course is just a vehicle for passing on those skills. So why can’t the curriculum flow naturally from where the instructor’s heart is?

When I think of teachers who have influenced me in the past, I rarely remember anything specific that they taught me — instead, I remember what sort of people they were, what they valued, and how they approached life. My education came simply from being in the room with them. Wouldn’t it be nice if, instead of taking English 101, a college student could take a course called “A Semester with Professor So-and-So”?

What a lovely surprise to see a post about one of my comments! I so wish students could enroll is A Semester with Professor So-and-So. That’s certainly what the best courses I’ve ever taken have felt like. I’m grateful that our decades long relationship has afforded me that opportunity with you!

Some additional thoughts on the obstacles.

I intentionally included the word “and” when I wrote “good at and enjoy doing” precisely because of the mismatch you point out.

I think spending time trying to figure out how objectively evaluate whether somebody is actually “good at” doing something takes us off purpose. I think that subjective evaluation is find and having the intent of moving in the general direction would result in huge transformations of how people spend their time.

I feel such sadness that the something I enjoy doing – storytelling of a personal nature – has an extremely negative impact on my father. As it stands now, a bunch of people are doing things they don’t enjoy doing that cause harm. I think that if people are doing things they enjoy doing, they have more spaciousness and generosity to think about the impact of what they do and more curiosity about how mitigate it.

The toilet cleaning problem you reference has been thought about by people far smarter than I am. The idea is that everybody is willing to clean a toilet once in awhile. And so there would need to be a system that results in that happening that people buy into. Garbage collection is more complicated because it requires skills and training. Perhaps there could be a service component to the society I’m dreaming about – like how Israeli youth have to serve in the military for two years.